Fighting Illini Features

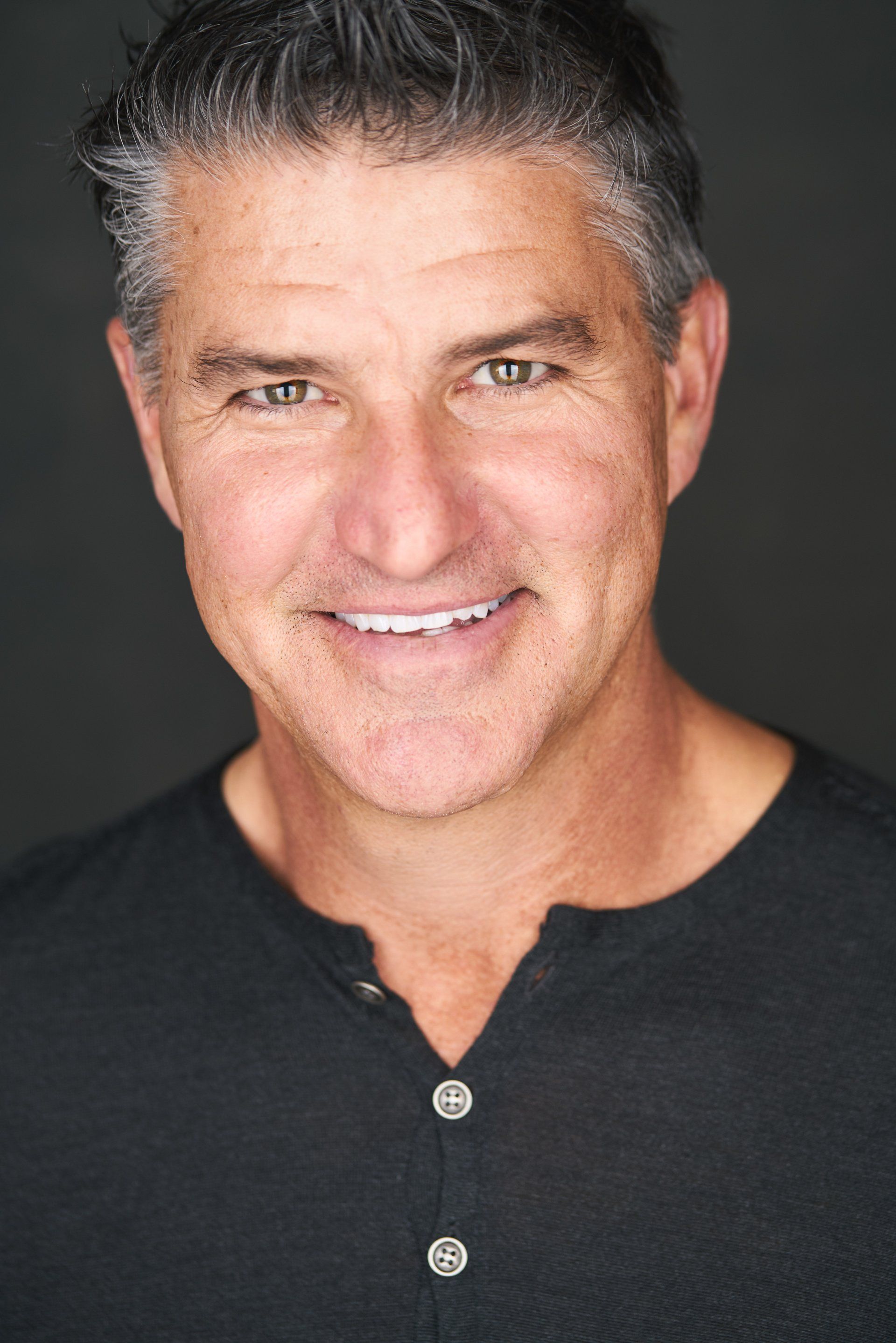

Current Illini stars

Current Illini Female Athletes Grateful to the Work of their Predecessors

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

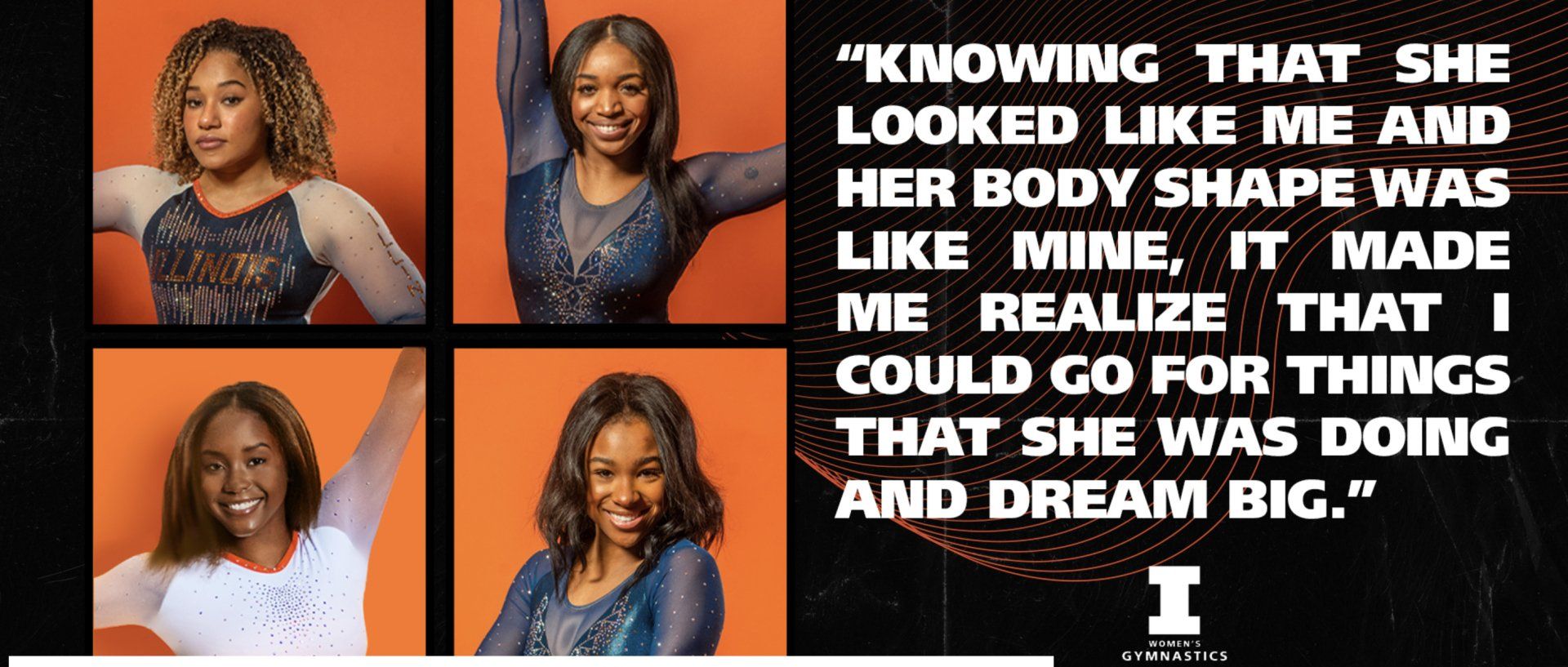

Three intellectually and athletically gifted Fighting Illini women's student-athletes—all born three decades after Title IX of the Education Amendment of 1972 was signed into law—admit that they've only read stories and viewed documentaries about the pioneering women who preceded them.

And yet, redshirt volleyball senior Diana Brown (Columbus, Ohio), track and field junior Noor Abdellatif (Antioch), and senior gymnast Mia Takekawa (Sacramento, Calif.) all share a sense of indebtedness.

"I mean, it's kind of crazy," said Abdellatif. "Just trying to be equal, they had to go through all those challenges and experience all of those hardships. They fought for what they wanted the outcome to be. It's just amazing how persistent they were."

Brown says that something worth doing is never easy.

"For women to be able to play sports back then, a lot of things needed to be broken down, including the stigmas and opinions," she said. "Compared to them, it seems like my life is really easy. There's so much in history that has been broken down and built up. To see where we are now, I appreciate what all has been built up. I think we can all learn a lesson from that."

Though Takekawa hasn't personally engaged with anyone who fought for women's rights in the 1970s and '80s, her cousin (Sarah Takekawa) played soccer at Saint Mary's College of California in the early 2000s. Over the years, Mia has heard some stories from her.

"I looked up to Sarah when I was thinking about college athletics," she said. "I've definitely had more financial privileges and a lot more media attention than she had 20 years ago. But, in terms of the people that paved the path for me here at the University of Illinois, it's definitely important to know where we started, where we are now, and where we still have to go."

Until just recently, the trio was unaware of what happened in April of 1977 when Illini track and field athletes Nessa Calabrese and Nancy Knop formally charged UI's Athletic Association with discrimination against women in the operation of its programs. The wide-ranging suit asserted that the AA spent six-and-a-half times more money for its men's sports than it did for its women's teams, awarded financial aid to male freshmen but prohibited it for women in their first year, and provided scholarship assistance to men over a five-year academic period as compared to only four years for women.

"It must have taken a lot of guts for them to do what they did, knowing that in that kind of environment back then that there could have definitely been backlash," Takekawa said. "Because of their actions, we are now able to have the privileges that we have today, to be able to compete and have equality. It is extremely important that today's athletes and women in general to be able to continue to speak out about things that still aren't necessarily equal."

And, in their opinion, how is the University of Illinois' current athletic department living up to those equity requirements today?

"As far as I can tell, women are getting equal treatment in terms of finances, but equality in benefits probably still has room for improvement," Abdellatif said. "For example, you don't see women's sports getting praised as much as the men's sports here. On social media, our successful women's sports deserve as much praise as say men's basketball. We'd certainly like people to follow women's sports more than they do."

"In our country," Brown added, "football and men's basketball are put ahead of every other sport. I totally understand that they bring in a lot of profit and that allows other sports to be part of the program. Our university has done a nice job in getting new (training) facilities for our softball and baseball teams. They do very well in taking care of us and I feel as though we are given a lot of the same opportunities, such as (access to) our athlete cafeteria. I think that our university tries as hard as they can to promote gender equality in a world where it's really hard to do that."

"Our coaches are great with their support, as is the rest of the staff with academics and financial assistance," Takekawa said. "Sure, the money-maker sports—football and basketball—have the facilities and all that, but we get new equipment when we need it. We may not get all the flashy things, but, day-in and day-out, we do get a lot of support."

Many women's student-athletes are still on the ground floor when it comes to the issue of name, image and likeness (NIL) benefits, though both Brown and Takekawa have had opportunities come their way.

I'm very appreciative of the opportunities I've gotten from Campus•Ink (apparel)," Brown said. "They are really trying to make it all about the athlete instead of just the clothing. I work closely with one of their designers and we're trying to come up with apparel that really, truly represents me. To be honest, I have high aspirations after my collegiate career ends, so I was kind of focusing more on that instead of pursuing the NIL deals that other athletes have."

Takekawa admits that her sport has one of the highest profiles among collegiate athletes regarding NIL.

"I've done a few deals, so I have been pretty lucky to be able to take advantage of NIL," Takekawa said. "Gymnastics is one of the few sports in which the women's side is more popular than the men's side."

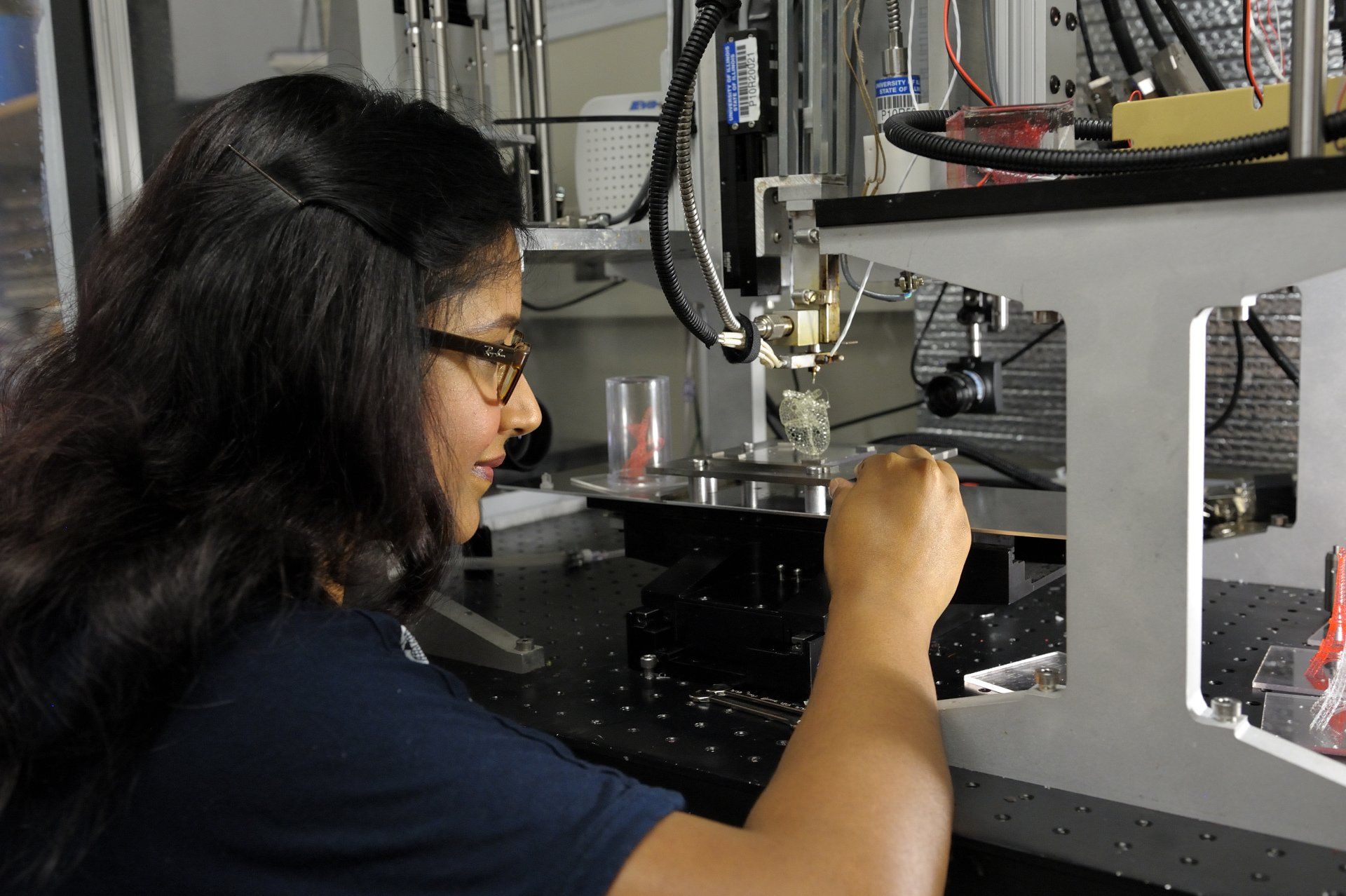

All three women are taking utmost advantage of their University of Illinois educations. Brown graduated last May, majoring in molecular and cellular biology and minoring in psychology. Abdellitif is studying kinesiology and hopes to become a physical therapist, while Takekawa is majoring in bioengineering and is on a track targeted towards therapeutics. Following her graduation in 2023, she'll pursue a career in pharmaceuticals.

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/8/31/title-ix-current-illini-female-athletes-grateful-to-the-work-of-their-predecessors.aspx

International Illini

Title IX’s Influx of Illini Women from the International Stage

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

Except for Antarctica, every other continent on Planet Earth has at one time been represented by women's athletes who've worn the Orange & Blue of the Fighting Illini.

The list of more than 100 Illini who've hailed from countries outside of the borders of the United States is headlined by Hall of Famers Lindsey Nimmo Bristow from England and Perdita Felicien Campbell and Emily Zurrer from Canada, but there are countless other foreign athletes who've also flown the University of Illinois' colors.

UI Director of Athletics Josh Whitman says that the international student-athletes with whom he's been associated seem humbled to have had the opportunity to compete in America.

"By and large, our international student-athletes are very grateful to be here," Whitman said. "It's fun to watch them grasp the American athletics experience and come to understand the platform they've been provided. They're a lot of fun to be around because they're incredibly humble and they're very motivated to take advantage of and really enjoy the full spectrum of the opportunity that exists in a place like Illinois. I think that anytime someone gets the chance to experience something that's truly different than what you're accustomed to or what you grew up knowing, it always gives you a different view on that opportunity."

Executive Senior Associate Director of Athletics and Senior Woman Administrator Sara Burton harkens back to the international student-athletes she encountered as a soccer player at Knox College.

"Certainly, what was modeled to me through their behavior and their words was that they weren't taking that opportunity for granted in any way, shape or form," Burton said. "They really looked to maximize that opportunity. And I think that is congruent with today's international student-athletes. I've worked with several personally. In fact, I have a thank you note here from one of my women's basketball student-athletes who shared a point of gratitude for our support of her around some specific travel needs related to her visa. That's something that doesn't go unnoticed with our international student-athletes. They take great pride in having an opportunity to compete and perform on behalf of Illinois. There's just a great deal of gratitude around those opportunities and they look to maximize them."

One of UI's very first international athletes who had an unusually high profile occurred in 1988 when Coach Mike Hebert added Bolsward, Holland's Petra Laverman to the roster. She earned first team All-Big Ten honors two years later. And two years after that, in 1992, Hebert threw a second net into The Netherlands to land first team All-American Kirstein Gleis.

The Illini track and field program has had a sizable number of foreign athletes. One of the very first was heptathlete Carmel Corbett Welso from New Zealand. She was a three-time All-American in the heptathlon and high jump. Canada has been especially kind to the Illini track program, sending future Olympians Felicien and Yvonne Mensah to Champaign-Urbana.

The Great White North has also dispatched top-notch athletes to soccer (Zurrer and Leisha Alcia), volleyball (Lorna Henderson), and other sports.

Besides Bristow, Europe's contributions to U of I athletics have included Swedish track Olympians Jenny and Susanna Kallur, Lithuanian volleyball standout Rasa Virsilaite and basketball starter Iveta Marcauskaite, and Czech Republic hoops star Petra Holesinska.

Among current 2022-23 Illini rosters, slightly more than a dozen current female student-athletes hail from foreign countries, including three swimmers (Suvana Baskar from India, Jenri Buys from South Africa and Paloma Canos Cervera from Italy), three basketball players (Geovana Lopes from Brazil, Aicha Ndour from Senegal and Liisa Taponen from Finland), three gymnasts (Amelia Knight from the United Kingdom, Mia Scott from England and Kiera Wai from Canada), and two Canadian soccer athletes (Ashley Cathro and Joanna Verzosa-Dolezal).

Former International Illini

Leisha Alcia (Canada), soccer

Sara Anastasieska (Australia), basketball

Camille Baldrich (Puerto Rico), tennis

Carmel Corbett Welso (New Zealand), track & field

Gayathri DeSilva (Sri Lanka), tennis

Ilkau Dikman (Turkey), swimming & diving

Perdita Felicien Campbell (Canada), track & field

Kirsten Gleis (The Netherlands), volleyball

Shivani Ingle (India), tennis

Yvonne Harrison (Puerto Rico), track & field

Lorna Henderson (Canada), volleyball

Nikita Holder (Canada), track & field

Petra Holesinska (Vracov, Czech Republic), basketball

Jenny Kallur (Sweden), track & field

Susanna Kallur (Sweden), track & field

Ashley Kelly (British Virgin Islands), track & field

Petra Laverman (The Netherlands), volleyball

Ashleigh Lefevre (Australia), soccer

Iveta Marcauskaite (Lithuania), basketball

Yvonne Mensah (Canada), track & field

Lindsey Nimmo Bristow (England), tennis

Pedrya Seymour (Bahamas), track & field

Kornkamol Sukaree (Thailand), golf

Pimploy Thirati (Thailand), golf

Rasa Virsilaite (Lithuania), volleyball

Emily Zurrer (Canada), soccer

Current International Illini

Suvana Baskar (India), swimming & diving

Jenri Buys (South Africa), swimming & diving

Paloma Canos Cervera (Italy), swimming & diving

Ashley Cathro (Canada), soccer

Siyan Chen (China), golf

Amelia Knight (United Kingdom), gymnastics

Geovana Lopes (Brazil), basketball

Aicha Ndour (Senegal), basketball

Mia Scott (England), gymnastics

Liisa Taponen (Finland), basketball

Tracy Towns (Canada), cross country/track & field

Joanna Verzosa-Dolezal (Canada), soccer

Kiera Wai (Canada), gymnastics

International Athletes in UI's Athletics Hall of Fame

Perdita Felicien Campbell was a three-time NCAA hurdles champion and was named 2001 and 2003 NCAA Track Athlete of the Year. She earned All-America honors 10 times while at Illinois. Felicien was a two-time world champion in the 100-meter hurdles and two-time world silver medalist. She set UI, Big Ten and NCAA records in 60 meter and 100-meter hurdles. Felicien represented Canada at 2000 and 2004 Olympic games and is a 10-time Canadian champion. She set the Canadian record in the 100-meter hurdles in 2004, which still stands today. Felicien was the first Canadian woman to ever win a medal at the World Championships. During her career, she won gold and silver at both the World Championships in the 100-meter hurdles and World Indoor Championships in the 60 meter hurdles. Felicien was inducted into the Athletics Canada Hall of Fame in 2016.

Lindsey Nimmo Bristow is the most acclaimed women's tennis player in Fighting Illini history after being named the 1993 Big Ten Player of the Year and earning All-Big Ten honors three times from 1991-93. Nimmo was the first Fighting Illini women's tennis player to earn All-America honors, doing so as a senior in 1993. A native of Sutton Coldfield, England, Nimmo also earned the Big Ten Medal of Honor in 1993 for excellence as both an athlete and student as she was named Academic All-Big Ten three times. She finished her Illini career as the school's record holder for career wins and wins in a season (48), compiling a career mark of 103-33 and season record of 48-7 in 1993 and was her team's most valuable player each of her final three years. Nimmo was named CoSIDA Academic All-American in 1993. Nimmo remains as Illinois' only Big Ten Player of the Year in women's tennis. She currently lives with her husband, Dal, in Naperville, Illinois.

Emily Zurrer earned All-America honors three times in 2006 (1st/3rd/3rd teams), 2007 (2nd/4th teams) and 2008 (3rd team), was a three-time First-Team All-Big Ten selection her final three seasons and selected to the All-Freshman squad in 2005. She was First-Team All-Region as a junior and senior. During her tenure on the back line, Illinois produced 42 shutouts and gave up the second-fewest goals in program history in 2008, allowing just 19. As a senior, Zurrer was the Big Ten Co-Defensive Player of the Year. She competed for Canada at the 2008 (starting every game) and 2012 Olympics, helping her squad to a bronze medal in 2012. Zurrer was the 2009 Big Ten Medal of Honor selection from Illinois. She played professionally in Sweden, Germany, Canada and the U.S., and now works as a realtor and fitness instructor in British Columbia, Canada.

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/8/17/general-title-ixs-influx-of-illini-women-from-the-international-stage.aspx

Jill Ellis

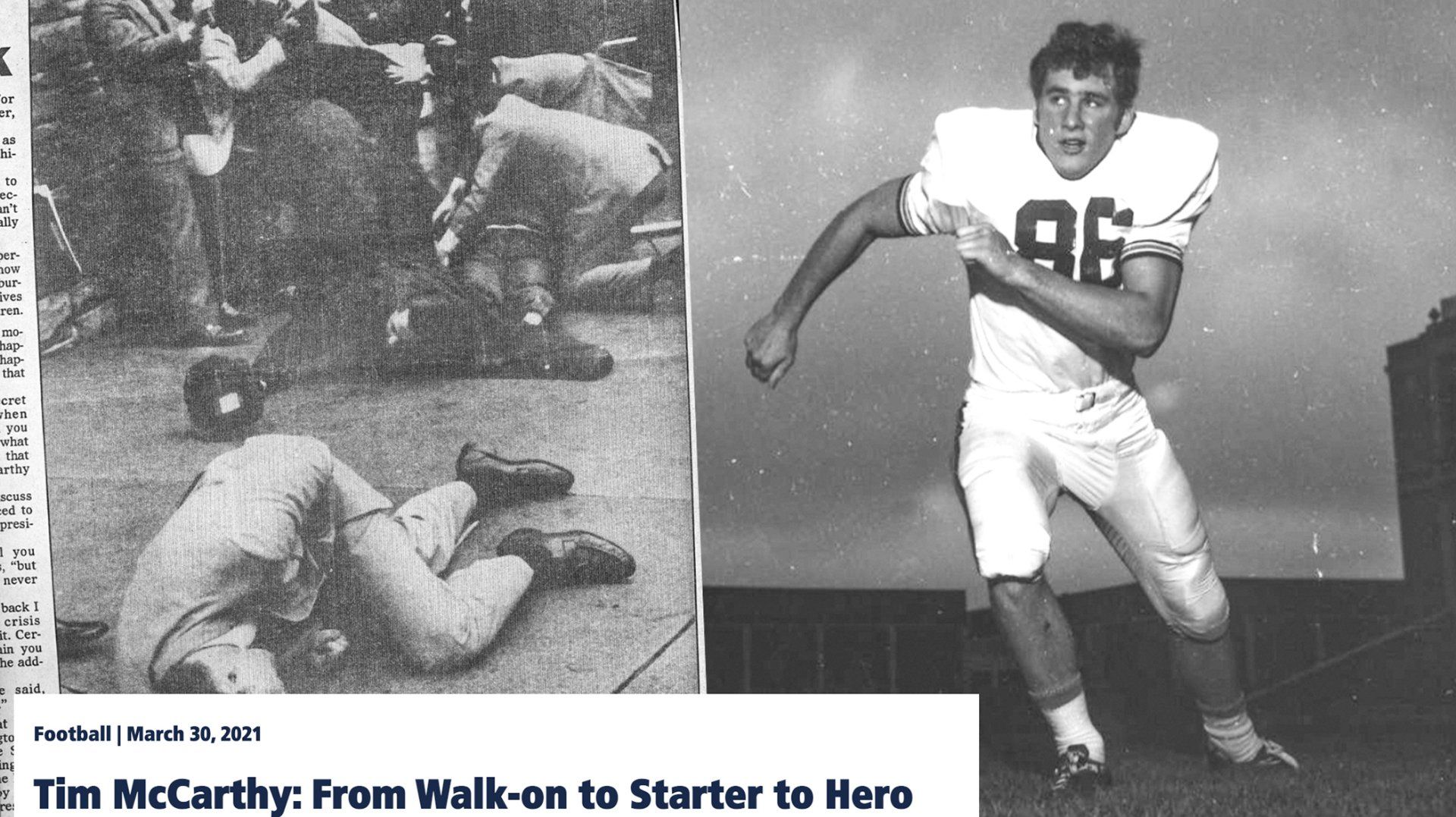

Jill Ellis’ Leap of Faith on Soccer Leads to Accomplishment-Filled Career

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

From her home near Portsmouth on England's southern coast, then five-year-old Jillian Anne Ellis was completely unaware as to how much a new American law called Title IX would eventually affect her life. At that time in 1972, all she knew was that she wasn't getting the same opportunity to play organized sports as her older brother, Paul.

Jill's life changed dramatically in 1981 when her dad, John, was offered the chance to move his family across the Atlantic and establish a soccer academy in the United States.

"I was 15 and about to go into my final year of school," Ellis remembered. "My parents said, 'Well, do you want to come with us to the States or would you rather stay and finish up here?' I said, 'Heck, I'm coming.' I was very excited to make the move."

Attending Fairfax, Virginia's Robinson Secondary School, Jill finally got the opportunity to play the sport that her father taught.

"When I first came over, I tried out for soccer and absolutely fell in love with it," she said. "You have to remember that soccer is the sport that every sports fan in Europe follows. It was neat for me suddenly going from being a fan to actually being a player."

Ellis excelled as a high school athlete and received an invitation to play soccer for the College of William & Mary, an institution founded in 1693 that was named after former English royalty. Receiving no financial aid until her senior season, it was strictly an opportunity to receive an education in her majors of English Literature and Composition.

Performing on the soccer pitch for the Tribe from 1984-87, Jill scored 32 career goals. As a senior, she was accorded third-team NSAA All-America honors.

The '80s were a time when women's collegiate sport was still sprouting, and female athletes received few frills beyond the ability to compete.

"We wore men's uniforms and had to buy our own cleats," Ellis recalled. "For our pregame meals, we were lucky if we went to McDonald's. It was on the very forefront of the evolution for women's soccer in college sports. However, there was a certain robustness and comradery of the athletes back then. You weren't playing for a scholarship; you were playing because you loved it. There wasn't any other motivation other than playing for the love of the sport.

"One of the things that really stood out for me was that there were no female coaches," Ellis remembered. "I mean zero. When I was playing, I don't recall ever competing against or having a female coach. In my senior year, we finally had a female assistant coach (April Heinrichs). It was literally the first time that I'd ever been coached by a female. The landscape was just barren in terms of coaching opportunities for women. Interestingly enough, I kind of fought against a coaching career initially. Soccer was more of a vehicle for me to get my education."

Soon came a career-changing moment for Ellis.

"I was working as a writer in North Carolina for a large tech company when April called me and offered me a coaching job," she said. "For a young person, I was making decent money. I had an apartment, I had heath care, I had a car. Still, I was really struggling with what I was going to do with my life. I remember calling my father and telling him that I'd been offered this coaching job for $6,000 a year. He was excited ... my mother not so much. But, for me, it was a moment of picking passion over paycheck. I took a leap of faith, jumped in with both feet, and never looked back because I absolutely loved it."

After three years as an assistant at Maryland, one at Virginia, and three more at North Carolina State, Ellis received an inquiry in the winter of 1997 from the University of Illinois about its head coaching position.

"I actually had gone home to Charlotteville to see my parents for the weekend," she remembered. "Dad left me a message that said Dr. (Karol) Kahrs had called from the University of Illinois. Full disclosure, I got out a map. There was no Google back then. I wanted to learn exactly where the school was and what kind of a school it was. I called Dr. Kahrs back. She said, 'We'd love to talk with you about our head coaching position and bring you out.' I went for a visit and I remember it was freezing cold. I met with Karol and I met with Ron, got to see what their plans were, and I really believed in their vision. The one daunting thing was that I had to put a team on the field in only about four or five months after I was hired. Looking back, had I been more thoughtful and more conservative, I probably should have thought that through. Ultimately, I liked what Ron and Karol pitched to me in terms of what we could build and I said 'Yeah, let's do this.'"

Ellis hit the ground running.

"I did a quick study and found out that there was a club team on campus," she said. "My plan was to get there as fast as I could and find out if there were some recruits who were still undecided. Once I got to campus, we held open tryouts with the club team. I was pleased with the core group. I looked for a certain level of athleticism and to identify those women who could play specific positions. The players were bright, resilient, passionate, and so appreciative of this opportunity. They went to the University of Illinois for the academics and, all of a sudden, they get to play a varsity sport with the inaugural team. That opportunity wasn't lost on them."

Ellis recalled the message to her players in one of the first meetings.

"I remember saying to the players, 'Listen, I'm going to be patient but I'm not going to lower my expectations,'" she said. "It was a message of we're going to be fit and we're going to be an aggressive team in terms of how we play. We're going to have tremendous work ethic and we're going to have each other's backs. I can't remember how many games we won that first year, but we celebrated the highs big time. It really was a great foundation on which to build ... great people with great character."

A sense of excitement abounded as the Illini approached their very first game on Sept. 5, 1997, against Loyola.

"I remember the players getting their uniforms and just being just so excited," Ellis said. "It kind of took me back to when I made my first team at (age) 15. Your jersey, when you make a team, is such a prized possession. Sure, there was a little bit of anticipation and anxiety, but one of the things that they bought into was 'We've got everything to gain and nothing to lose.' So we took the field with a very attacking mindset."

The Illini opened up with victories in their first four games, but then lost the next seven in a row. That set the stage for a Big Ten battle in mid-October against Northwestern, a match in which the Illini prevailed by a score of 3-2 in double overtime. It was a particularly memorable moment in that inaugural season.

"That was definitely a dog-pile game," she said. "As a coach, you're just so happy for the players because you know (the effort) they'd put into the game."

In May of 2022, 24 years after the eventual two-time World Cup Championship coach of Team USA departed Champaign-Urbana for a job at UCLA, Ellis received an invitation to speak at the U of I's Commencement ceremony.

"It was serendipity," she said. "It was getting back to where it had all begun and an appreciation of coming back to where I'd cut my teeth and planted my feet in the coaching ranks in terms of making it my profession. It was a huge honor. I was so privileged and proud to come back during the celebration of Title IX's 50th anniversary. It was an acknowledgment and a tip of the hat to the University for adding this sport and continuing to grow the game of women's football. Coming to America was an absolute life-changing moment for me. Growing up in England, never would I have dreamed of having a career in sport."

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/8/10/jill-ellis-leap-of-faith-on-soccer-leads-to-accomplishment-filled-career.aspx

Eichelberger Field

The Women of the 2000s: Softball Begins and a Flurry of All-Star Performers Headline the Beginning of the 21st Century

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

The much-awaited new millennium introduced an additional sport to the University of Illinois' varsity women's athletics lineup, but plenty of other prominent storylines occurred during the first 10 years of the 21st Century.

About one year after softball made its debut in March of 2000, Eichelberger Field became the home for a plethora of talented athletes.

Women's golf got a big boost in 2004 when construction of the Demirjian Indoor Golf Practice Facility was announced. A beautiful new tennis area, the Khan Outdoor Complex, followed three years later.

Individually, names like Felicien, Alcia, Hunt, Mensah and Bizzarri grabbed multiple headlines.

Here is a chronological look at several of the most memorable Illini women's moments from 2000-09.

Jan. 2, 2000: Women's basketball romped past No. 5 Georgia, 82-65, at the Assembly Hall.

Mar. 11, 2000: UI's softball team made its varsity debut, splitting a doubleheader at Coastal Carolina. Due to the lack of a home field, Coach Terri Sullivan's players were never seen by the majority of Illini faithful.

Mar. 17, 2000: Illini women's basketball defeated Utah in an opening-round game of the NCAA Tournament, 73-58.

Apr. 15, 2000: Groundbreaking ceremonies for Eichelberger Field.

June 13, 2000: Sophomore Jessica Aveyard, Illinois' first-ever swimming All-American, won the Dike Eddleman Award as UI's top female athlete.

Aug. 31, 2000: Karol Kahrs retired after 36 years of service.

Sept. 15-Oct. 1, 2000: At the Olympics, Illini swimmer Ilkay Dikman (Turkey) and Perdita Felicien (Canada) competed for their home countries.

Nov. 8, 2000: Illinois soccer played and won its first-ever NCAA Tournament game, defeating Xavier, 2-0.

Mar. 15, 2001: Illini women's swimming and diving made its very first appearance in the NCAA Championships, ultimately tying for 35th place.

Mar. 30, 2001: In its first-ever Big Ten games, Coach Terri Sullivan's Illini softball team swept Michigan State, 4-1 and 10-2. Illinois finished with a 12-8 conference record.

Apr. 27, 2001: UI's 4x100-meter shuttle hurdle relay quartet of Jenny Kallur, Camee Williams, Susanna Kallur and Perdita Felicien set a world record (52.85) at the Drake Relays.

Apr. 29, 2001: Illini women's tennis nipped Northwestern for the Big Ten title.

May 1, 2001: Volleyball's Betsy Spicer was named the female recipient of the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor.

May 10-12, 2001: At Ann Arbor, Illini softball went 2-2 in its very first Big Ten Tournament.

May 12, 2001: Illini tennis beat Virginia Commonwealth, 4-2, to claim its first NCAA Tournament victory.

May 19, 2001: Perdita Felicien ran the world's fastest time in the 100-meter hurdles (12.75).

Nov. 26, 2001: Don Hardin named Big Ten volleyball's Coach of the Year; senior Shadia Haddad named conference's Big Ten Defensive Player of the Year.

Dec. 28, 2001: Illini women's basketball topped No. 12 Michigan, 85-81, at Ann Arbor.

March 8, 2002: Sixty-meter hurdler Perdita Felicien captured UI track and field's first-ever NCAA indoor title with a collegiate-record time of 7.90.

May 6, 2002: Illinois' Jessica Aveyard named Swimmer of the Year by the Illinois Swimming Association.

May 10, 2002: Shortstop Lindsey Hamma and outfielder LeeAnn Butcher became Illini softball's initial first-team All-Big Ten selections.

June 1, 2002: Perdita Felicien wins the NCAA 100-meter hurdles title.

Oct. 12, 2002: Illini volleyball topped Coach Mike Hebert's sixth-ranked Minnesota Golden Gophers, 3-2.

Nov. 7, 2002: Illini soccer defeated No. 11 Penn State, and four days later beat No. 13 Purdue.

Jan. 10, 2003: UI's Allison Prather set the UI record in one-meter diving (270.85).

Jan. 26, 2003: Illini women's basketball defeated 10th-ranked Minnesota, 94-80, in Champaign.

Feb. 23, 2003: Illini women's tennis team shocked top-ranked Duke, 4-3.

May 15, 2003: The Illini softball team captured the program's first-ever NCAA Tournament victory, a 5-3 win over Georgia Tech.

June 14, 2003: Perdita Felicien won the NCAA 100-meter hurdles crown with a time of 12.74.

June 26, 2003: Illini athletes swept both the Big Ten's Jesse Owens Male and Suzy Favor Female Athletes of the Year awards. NCAA tennis champ Amer Delic and wrestling titlist Matt Lackey shared the prize for the men, while NCAA hurdles champ Perdita Felicien was the women's award winner. The trio was named UI Athletes of Year on June 4.

Aug. 28, 2003: Perdita Felicien registered victory in the 100-meter hurdles at the World Track & Field Championships.

Sept. 23, 2003: Former Illini great Tonja Buford-Bailey was hired as UI's assistant track coach.

Nov. 9, 2003: Illini soccer prevailed over Michigan, 2-0, to win the championship game of the Big Ten Soccer Tournament, its first-ever conference title.

Nov. 21-23, 2003: Illini women pioneers, including some from the 1930s, gathered on campus for the 3D Celebration reunion.

Dec. 12, 2003: Illini soccer goalkeeper Leisha Alcia named an All-American.

Feb. 20, 2004: Ilkay Dikmen broke Illinois swimming's 100 breaststroke record (1:02.11).

Apr. 3, 2004: Illini gymnast Cara Pomeroy posted the school's first-ever perfect score, a 10.0 on the parallel bars at the NCAA South Central Regional.

Apr. 17, 2004: Illini softball beat No. 9 Michigan, 3-2, to claim its first-ever victory over a Top Ten team.

Aug. 22, 2004: Illini track and field alumnae Susanna Kallur (Sweden) and Perdita Felicien (Canada) competed in the Olympics, advancing into the 100-meter hurdles semifinals.

Sept. 11, 2004: Coach Don Hardin's Illini volleyball team upset top-ranked Southern California in five sets at the Illini Classic.

Sept. 18, 2004: UI held groundbreaking ceremonies for its Demirjian Golf Practice Facility.

Oct. 30, 2004: Illinois' Cassie Hunt won Big Ten cross country's individual championship.

December 2004: In the month of December, Illini women's basketball traveled to Louisiana State and defeated the 21st-ranked Bulldogs, 71-65 and then followed up with a 78-63 win over No. 16 UCLA.

May 3, 2005: Tennis standout Cynthya Goulet won the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor.

May 15, 2005: Illinois won the Big Ten Women's Track and Field Championships for the fifth time in its history. There were three individual championships and five second-place finishers.

Oct. 30, 2005: Women's cross country's Cassie Hunt won the 2005 Big Ten title with a time of 21:00. As a team, the Illini placed second.

Feb. 18, 2006: Illini swimmer Barbie Viney won UI's first individual Big Ten title in 24 years, posting a record time of 49.06 in the 100 freestyle.

Feb. 26, 2006: UI's Yvonne Mensah was named Athlete of the Meet at the Big Ten Indoor Track & Field Championships.

Apr. 6, 2006: Longtime Illini women's golf coach Paula Smith announced retirement. On June 8, former Illini Renee Heiken Slone was named as Smith's replacement.

May 2, 2006: Soccer star Christen Karniski named female winner of the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor.

June 1, 2006: Softball star Jenna Hall became Illinois' first-ever All-American. She ended her record-breaking season with .481 batting average, a .651 on-base percentage and an .847 slugging percentage, all UI records.

Oct. 1, 2006: Two goals by Ella Masur rallied the Illini soccer to an upset win over No. 9 Penn State, 3-2.

Mar. 22, 2007: In Theresa Grentz's final game as Illini coach, host Kansas State beat Illinois, 66-51.

Apr. 20, 2007: Groundbreaking ceremony for UI's Khan Outdoor Tennis Complex.

May 11, 2007: Jolette Law, longtime assistant coach at Rutgers, was named head coach of the Illini women's basketball team.

May 13, 2007: Illinois tied for the Big Ten women's outdoor track and field title, 129-129 with Michigan. Yvonne Mensah captured four gold medals, winning the 100, 200 and triple jump, as well as anchoring UI's victorious 4x100 relay.

Feb. 16, 2008: Illini softball upset UCLA, 6-2, handing the Bruins one of only nine losses they'd incur that season.

Mar. 7, 2008: Clutch free throw shooting by Lori Bjork and Rebecca Harris clinched a 68-64 Illini women's basketball win over top-seeded Ohio State at the Big Ten Tournament, qualifying Illinois for the championship game.

Apr. 4, 2008: Longtime women's track and field coach Gary Winckler announced that he would step down. Tonja Buford-Bailey was designated as Winckler's replacement.

April 24, 2008: Allison Buckley became first Illini women's gymnastics' first All-American.

Apr. 25, 2008: Illini women's tennis stunned Ohio State in the Big Ten Championship quarterfinals.

Apr. 30, 2008: Illini shortstop Angelena Mexicano crushed her 24th home run of the season to break the Big Ten single-season record.

Nov. 16, 2008: Illini soccer beat Missouri in game two of the NCAA Tournament on penalty kicks.

Nov. 24, 2008: The Illini women's cross country team placed 10th at the NCAA Championships.

Dec. 1, 2008: Volleyball coach Don Hardin announced his retirement. Eleven days later (Dec. 12), his coaching era ended with a third-round NCAA Tournament loss to California.

Aug. 8-24, 2008: Susanna Kallur (Sweden) and Emily Zurrer (Canada), competed in track and field and soccer, respectively, at the Olympic Games.

Jan. 8, 2009: Illinois named Kevin Hambly head volleyball coach.

Apr. 16, 2009: Illini women's gymnastics made its first-ever appearance at the NCAA national championships, placing 12th. UI's Bob Starkell was named as the nation's Women's Coach of the Year.

June 11, 2009: Emily Zurrer, Illini soccer star, won the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor.

June 13, 2009: Angela Bizzarri captured UI's first-ever NCAA title in a distance event (5,000 meters in time of 16:17.94).

Aug. 6, 2009: Former Illini coach Gary Winckler was named to the USTFCCCA Hall of Fame.

Oct. 16, 2009: A crowd of 7,632 watched rookie coach Kevin Hambly's 10th-ranked Illini sweep past former coach Mike Hebert's No. 6 Minnesota Golden Gophers in Big Ten action at Assembly Hall.

Nov. 23, 2009: Angela Bizzarri won the NCAA individual national championship, earning her National Cross Country Athlete of the Year honors (Nov. 25) and the Honda Award (Dec. 9).

Dec. 16, 2009: Volleyball's Laura DeBruler was named a first-team All-America.

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/8/4/general-the-women-of-the-2000s-softball-begins-and-a-flurry-of-all-star-performers-headline-the-beginning-of-the-21st-century.aspx

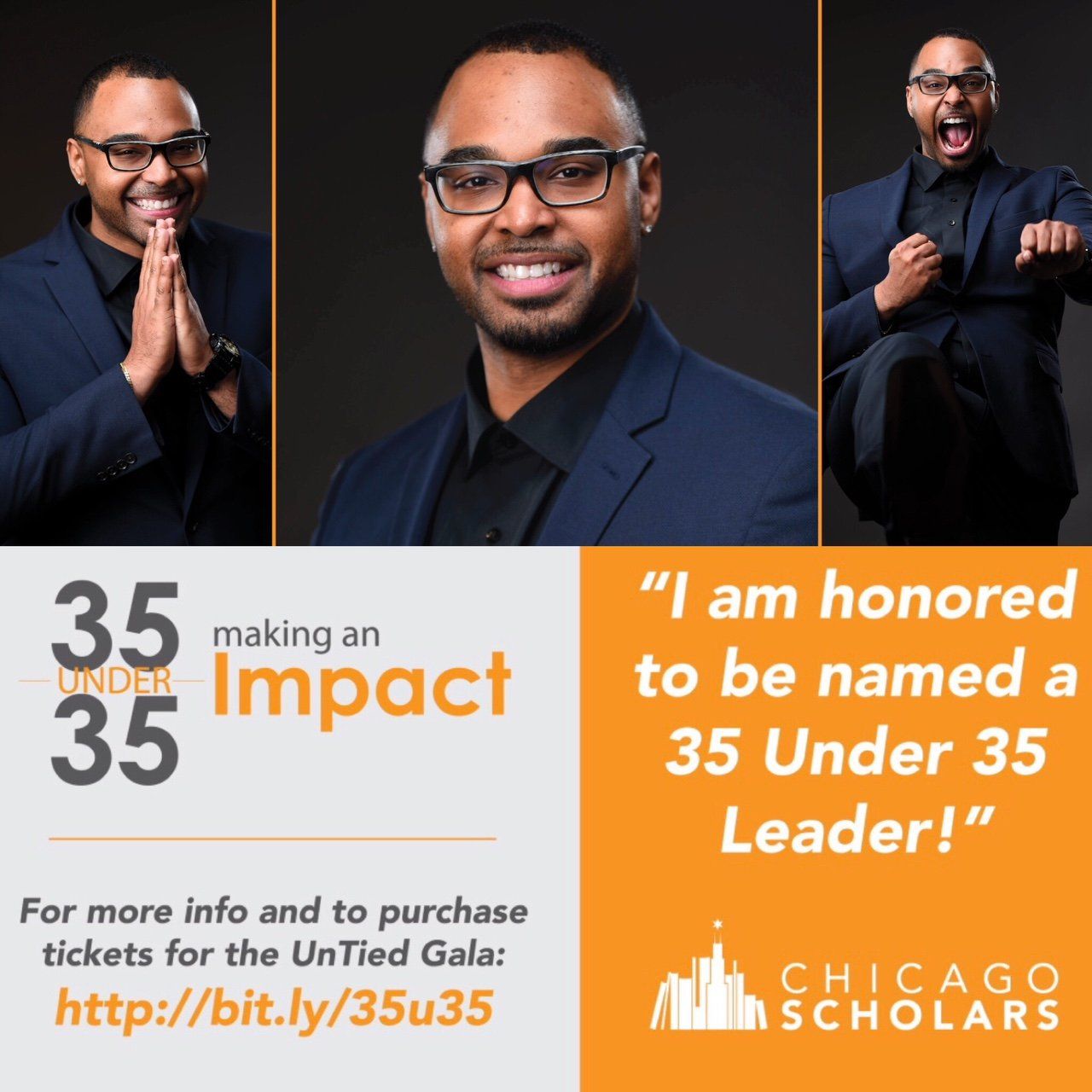

Kate Riley Smith

KATE RILEY SMITH: Living Your Life Legendary

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

Though her closet is now filled with more items featuring purple and white, former Illini basketball standout Kate (Riley) Smith proudly treasures her undergraduate education at the University of Illinois as a primary reason for the success she's enjoyed during her prestigious career in business and higher education.

Today, Smith's title at Northwestern University is Assistant Athletic Director for Career Enhancement and Employer Relations. She directs the Wildcat athletic department's NU for Life Program.

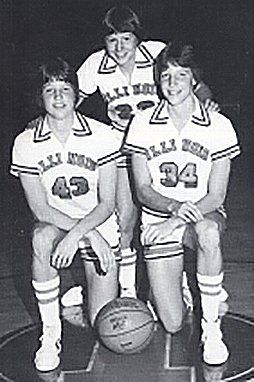

The Edina, Minn. native lettered twice as a forward for Coach Laura Golden (1989 and '90) and twice for Coach Kathy Lindsey (1991 and '92). She also shined in the classroom. So exceptional was Smith as a business administration major that Illini administrators named her as the school's female honoree of the Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor in 1992.

That award is one of the most precious jewels on Smith's glittering resume.

"I was recently part of an awards ceremony at Northwestern," she said. "I realized there are only 28 student-athletes out of 9,000 in the Big Ten that win the Conference Medal of Honor. Thirty years ago, it would have been only 20. The prestige of this award is such an honor and one that I certainly did not expect or anticipate. I had no idea that I was being considered. It's something I will forever be grateful. I had always prided myself in being both a student and an athlete. I had always been a very dedicated student, so to be acknowledged among all of your peers ... to this day there's a little bit of 'how did that happen?'"

Upon her graduation from UI's College of Business, Smith was focused on developing a career in corporate marketing. Following a brief period in commercial real estate, she ultimately worked for some of America's consumer biggest brands.

"My dream was to work in marketing at the intersection of sports on the consumer side of business," she said. "Marketing is about influencing attitudes and opinions about brands, and I was intrigued by that."

Smith opted to pursue her MBA at Northwestern's Kellogg School of Management and it proved to be a real game-changer for her, accelerating her path in marketing. During a 14-year career with Proctor & Gamble, General Mills and PepsiCo, she eventually advanced to become senior director of marketing for Gatorade.

A decade ago, Smith pivoted in her career and returned to Northwestern to become the Kellogg School's Assistant Dean for Admissions and Financial Aid. She remained in that position until September of 2021.

Coming Full Circle

With the emergence of COVID and after 10 years of working in admissions, Smith began to imagine a career that eventually brought her full circle.

Last February, NU Vice President for Athletics and Recreation Dr. Derrick Gragg brought Smith on board to join his Wildcat athletics staff.

"In my own journey, I have so appreciated all of those people who helped develop me and my career path," she said. "Just as all the schools in the Big Ten have such great cultures and communities, the culture at Northwestern is fantastic as well. I most enjoy sitting with the student-athletes and talking about their goals, their dreams and helping them map out their potential career. It's kind of full circle, being back at a Big Ten institution."

In April of 2017, on the 25th anniversary of Smith winning the Big Ten Medal of Honor, she returned to Champaign-Urbana to speak to Illinois' student-athletes at the OSKEE Awards.

"As I was writing my speech, I wanted to say thank you to some of the people who had shaped and influenced who I was," she said. "That brought me to Jenny Arnold, a 12-year-old girl who was my super fan during my playing days as an Illini. For some reason, she decided that I was her favorite. She made signs and celebrated me. I got to know her and, for at least a decade, ultimately became a pen pal of her after I graduated. When Jenny became a young woman, we fell out of touch. As I wrote the speech, I was determined to find her and see what she was doing. I discovered that she had passed away from breast cancer. When Jenny developed terminal cancer, she wrote a book that was titled 'Learning to Live Legendary.' What her message was for me was doing whatever you want to do in life and do it in a way where you make an impact and help and support others.

"To me, legendary doesn't mean infamy," Smith continued. "It means that you're doing something that has a positive impact on the world around you. As I was giving the speech that night, one of the student-athletes in the audience recognized that Jenny's sister was her Fellowship of Christian Athletes' advisor. Her sister (Sara Arnold Hurst) and I eventually had an hour-long conversation about Jenny and her adult life, becoming a mom and what it was like to lose her. It was just an amazing moment to have that reconnection through her sister. Jenny had chosen me as someone that she admired."

"This is where sports provide you with experiences, connections and opportunities that I don't think come organically in other ways," Smith said.

Education is Everything

"To me, education is everything," she said. "Obviously, I pursued my master's and I've been able to meet and work with so many people who have pursued master's degrees across different fields of study. My former dean had a great quote that said 'Who said that 21 is when you should stop learning?' Education is crucial in terms of opening your mind and teaching you critical thinking skills in whatever you study. What you study aligns more with your interest areas but the process of learning and expanding your understanding of the world around you are so important.

"You'll not compete as an elite athlete for your entire life," Smith continued. "At some point you'll pivot in another direction. What you invest in your education helps prepare you for that moment. In terms of living your life legendary, how can you apply the skills and talents that you possess and give back to the world and community around you?

"I have experienced the value of my education both at the University of Illinois and at Northwestern," she said, "and I wouldn't trade it for the world."

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/7/27/womens-basketball-kate-riley-smith-living-your-life-legendary.aspx

Terri Sullivan

Softball Early Years: Guiding the Program Off the Runway and Into the Sky

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

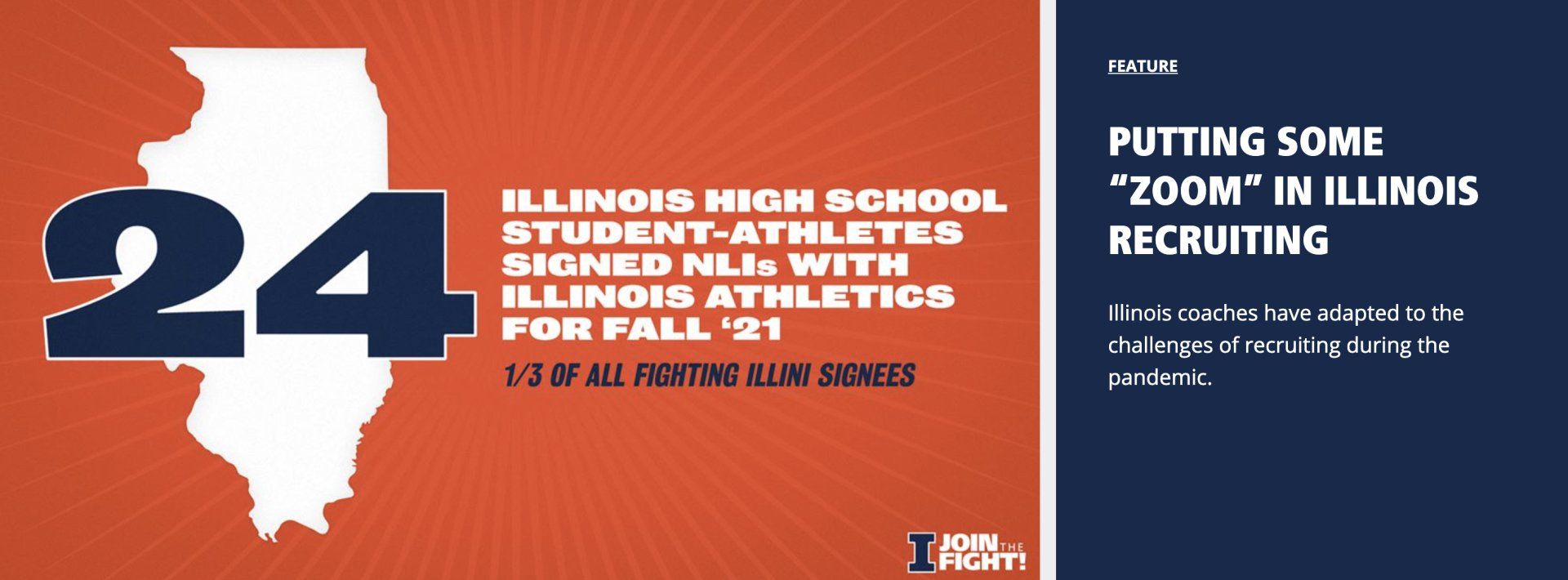

In 1998, when Illinois Athletic Director Ron Guenther announced that women's softball was being added to the University of Illinois athletics' menu, it became the last program among the Big Ten's longtime members to join the party.

Two years after the Illini introduced soccer to its fans, softball became Illinois' 10th women's varsity program, filling a void in a state long known for its girls' fastpitch excellence.

"Illinois is a great softball state," Guenther told the Decatur Herald & Review. "It's in the city, in the suburbs, downstate ... it's everywhere."

The Illini AD's next step was to identify the sport's first Illini coach. Interest in heading up UI's program was significant, but youthful UIC assistant coach Terri Sullivan had been planting seeds about her interest for a while with Guenther.

"I had heard rumors that the University of Illinois would possibly be starting a softball program," Sullivan said. "I began sending letters and Ron was forwarding them on to Karol Kahrs, just letting them know who I was. They always got back to me and always had something positive to say."

Finally, Guenther set up an in-person meeting with Sullivan.

"We were hosting regionals at UIC at the time and I met with Ron in Chicago about the position," Sullivan said. "We talked about what it would take to build a program from the ground up and he mentioned that he wanted a person with a lot of energy to get it off and running. I could tell that he was a coach's coach. And, lo and behold, I got the position. It was exactly the challenge I was looking for. I was just 29, but they had a lot of faith in me."

Sullivan was introduced at a mid-July press conference in 1998, then immediately hit the recruiting trail.

"I remember telling Ron that I had to leave the next day to recruit," she said. "One of the biggest recruiting tournaments for college coaches was taking place in Colorado. Nearly every coach was going to be there. Rick (Raven), our equipment manager, gave me (Illini) polos to wear that were down to my elbows. I remember those first recruiting letters included (the phrase) 'building something from the ground up ... and being the first team to make history'. Our pitch was that you could go somewhere where things are already built or be a part of building something. They had to determine what was the best fit for them. It was a message that I really believed in. Besides talent, we wanted to identify players who were dedicated, coachable, enthusiastic, unselfish, etc. The people component was a big part of it for us."

Another important question the Sullivan had to immediately answer was whether Illini softball would actually field a team during the 2000 season.

"I had brought along Donna DiBiase who had been a player and a graduate assistant at UIC," Sullivan remembered. "We decided that we wanted to play. Illinois had (fielded) a club team for some time and it didn't take long for me to see that those girls were competitors who would run through a wall for you. We had something like 140 kids try out for the team and we picked enough players to play that first season. We just had the time of our lives. It was just an amazing group of young women who were on that team from the club sport and also a few who were originally there for academic reasons but who had played high school softball."

Sullivan was well aware of the extreme talent level that Big Ten softball presented.

"There were some dominant programs in the Big Ten," she said. "Our initial goal was to compete our way into the middle third (of the conference) and then, hopefully, by year three, winning at the upper echelon. Those were lofty goals, but we never wanted to use the youth of our team as an excuse. Everybody knew it; we didn't need to tell anyone. We didn't want that to be a crutch when we took the field. I've always been a big believer in playing a monstrous, aggressive schedule. `That directly comes from my father (former Depaul and Loyola coach and AD, Gene Sullivan)."

Sullivan's 2000 Illini squad posted a respectable 13-17 record and that group was greatly enhanced in 2001 by a 15-person recruiting class that included future stars Amanda Fortune, Lindsey Hamma, Erin Jones, Janna Sartini, Erin Montgomery, Sarah Baumgartner, Katie O'Connell, Lindsey Tanner, Alicia Hammel and others.

"We had some terrifically talented players, players from state championship teams that wanted to be part of firsts," Sullivan said. "That recruiting class just had it in them. It's a prime example of how a together team can really do great things. No team ever intimidated them. It was just really fun to be a part of. If there was a challenge going on and you were playing a team that, on paper, you're not supposed to beat, we always tried to tell our players to be serious but have fun. It's going to be demanding, but we're going to have fun. We're going to be dedicated and disciplined but have fun."

The program's initial monumental victory came on Feb. 23, 2001, when Illinois visited 16th-ranked Florida State.

"Coach (JoAnne) Graf was a Hall of Fame coach at Florida State," Sullivan said. "Before the game, she told me that it was going to take a while, but to be patient and that we'd get there. In talking to the team before the game, I relayed about what she'd said and I tried to create a little bit of fire. Well, we had some real competitors on that team. I remember Katie O'Connell kind of looking at me and saying 'What are we supposed to do for the next four years?' Well, we went on to beat Florida State in that game (1-0 in eight innings) and it really set the stage for what Illinois softball would become ... playing pitch-by-pitch, inning-by-inning, believing in yourself, and having a positive attitude and energy. We did go on to have some success (a 49-23 record) but we didn't get an NCAA bid that year or the next year. We thought we had earned it and had worked hard to be competitive with everybody. The challenges were all fun ones. It's all about the players and any success the coach has comes from them. For me, to be around young people and trying to motivate and inspire them, all of the challenges were worth it."

Years later, Sullivan remains indebted to donors Lila Jeanne "Shorty" Eichelberger and Rex and Alice Martin for their generosity in establishing Illinois' Eichelberger Field and the Martin Softball Complex. The facility debuted on Mar. 27, 2001.

"Shorty was much more than a donor," Sullivan said. "She traveled with us on the road and she became our No. 1 fan. And the Martins ... well, you just couldn't ask for better people for our team to be around."

Sullivan stepped down from her role as the Illini coach following the conclusion of the 2015 season to focus on her family. DePaul's current Assistant Director of Athletics of Academic Advising, wife of former Illini football star and administrator Shawn Wax, and the mother of a 12-year-old daughter and two older stepdaughters, says that the sky's the limit for future softball players.

"The athletes today have incredible access to training facilities and coaches and competition," she said. "My parents always told me that you can't be what you can't see. And now you're seeing women coaching at all levels, both in male and female sports, and the door has been opened for female executives. The opportunities to work, to teach, to coach and then get rewarded for it are tremendous."

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/7/20/softball-early-years-guiding-the-program-off-the-runway-and-into-the-sky.aspx

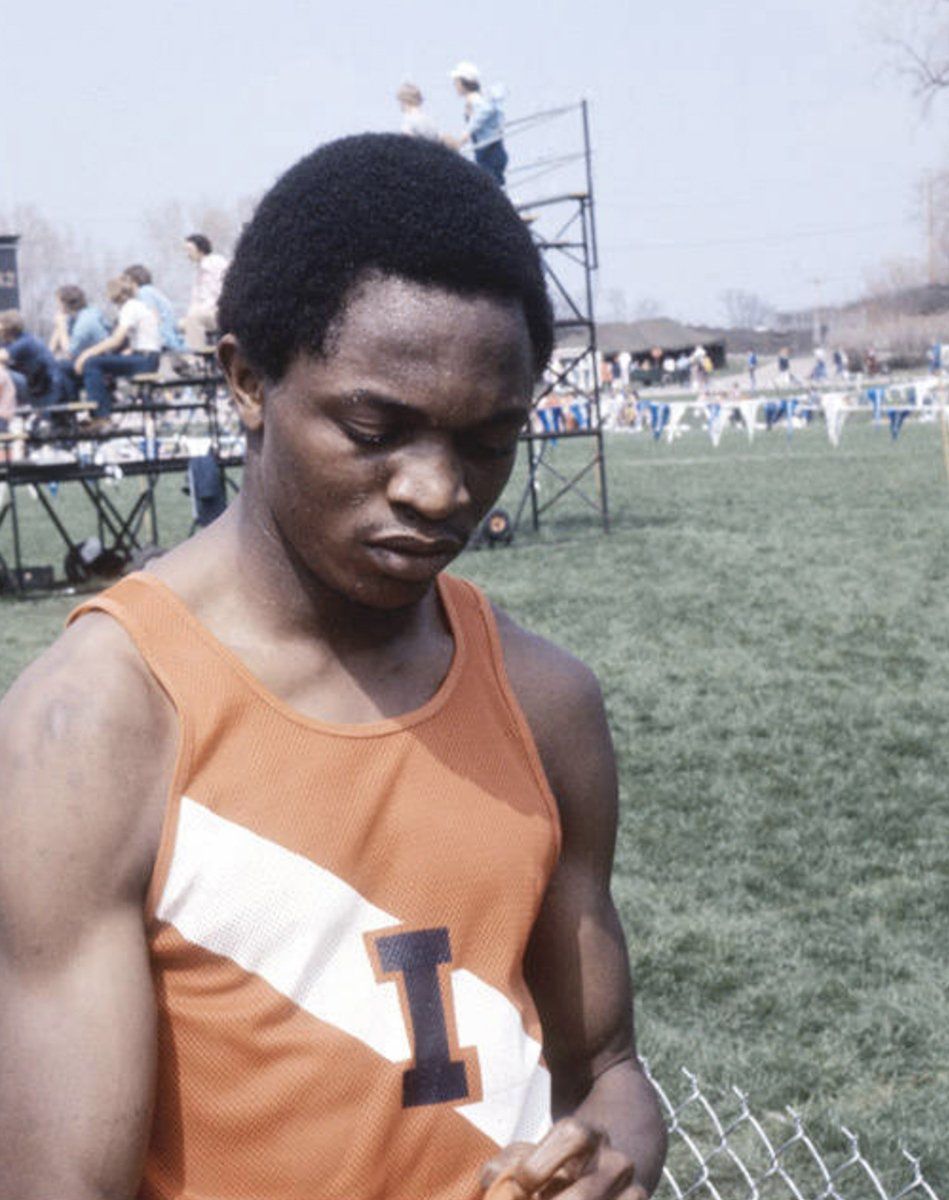

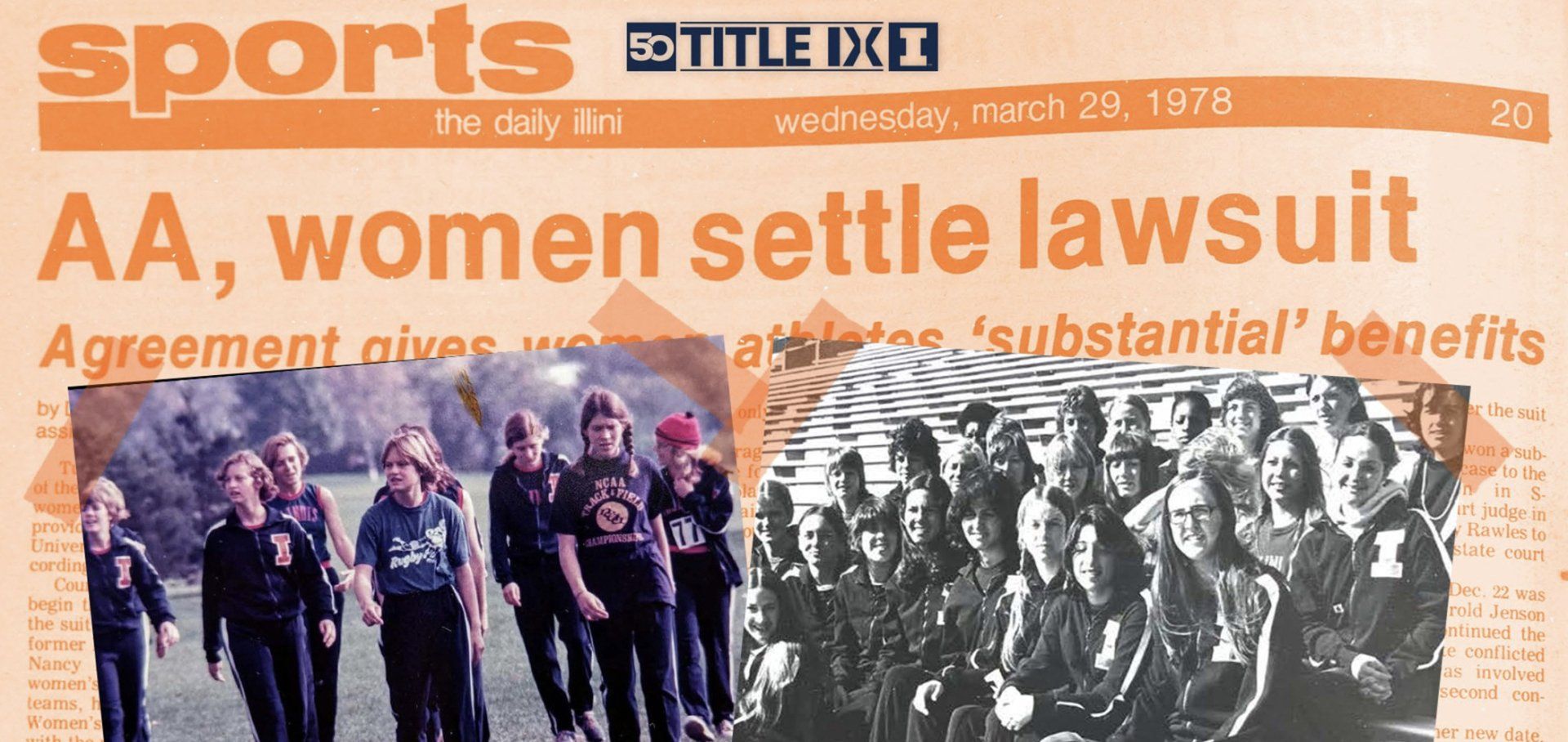

1978 Lawsuit

When Courage Moved the Needlefor Illini Women's Athletics

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

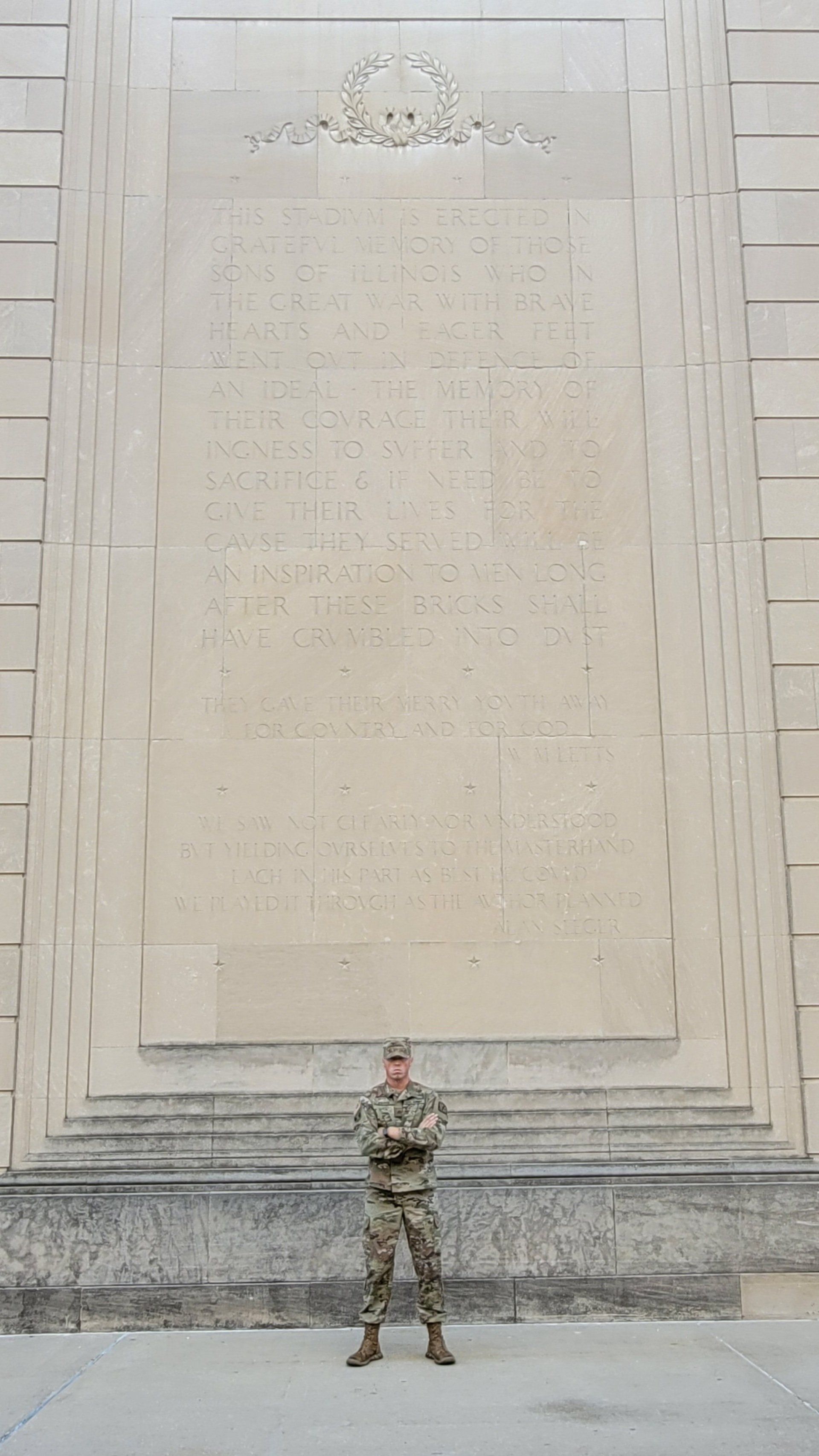

While the addition of seven varsity-level sports in the Spring of 1974 was undoubtedly a milestone moment for women's athletics at the University of Illinois, Title IX historians will argue that a more significant moment occurred three years later when a pair of courageous student-athletes filed a lawsuit charging sexual discrimination.

On April 11, 1977, at Circuit Court in Urbana, Nessa Calabrese and Nancy Knop charged UI's Athletic Association with discrimination against women in the operation of its programs. The multi-faceted suit contended that the Association spent six-and-a-half times as much for men's sports as for women's teams, awarded financial aid to male freshmen but prohibited it for women in their first year, and provided financial aid for men over a five-year academic period but for only four years for women.

There were additional complaints as well, according to Calabrese, all based on unequal treatment between women and men's athletes.

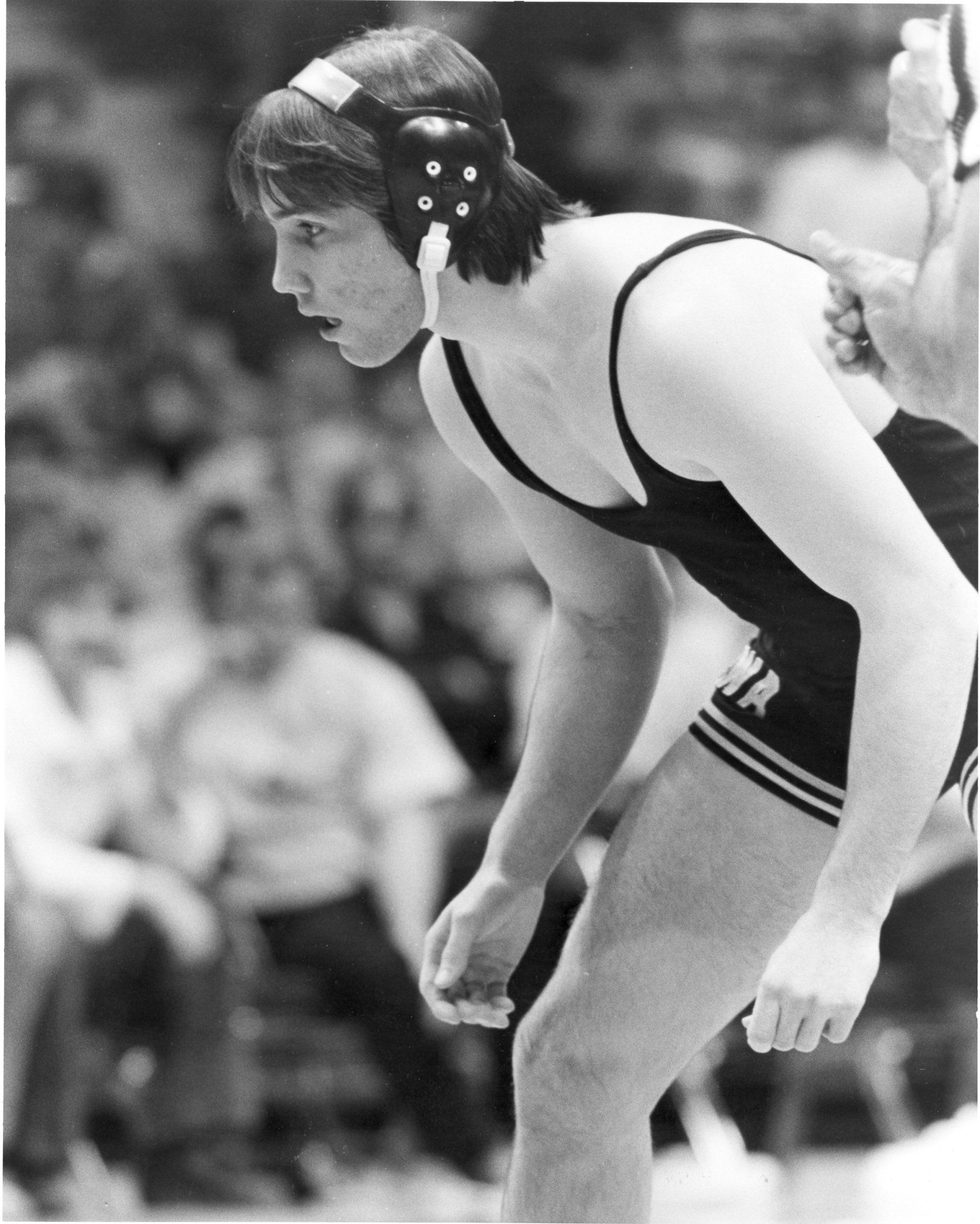

"Volleyball was my passion," said Calabrese, the former Illini two-sport star. "In those days, and I hope now, too, to play sports in college you have to be passionate about sports. There was so much sacrifice involved. We were only allowed to practice a few times a week because there were no facilities. At the gym in which we were practicing, you could barely keep the ball in play because the ceiling was so low.

"Track and field was kind of the same way. You're competing in the discus ring at the track in the stadium, but you're practicing somewhere else like a corn field. We were setting up little flags trying to figure out what's 120 feet or what's 150 feet. People grumbled and complained and tried to move the needle but were basically unable to do so. So, regarding access to facilities, it was even worse."

It was much the same in the weight room.

"Women did not have access to the weight room at the stadium," Calabrese said. "Weightlifting is a big part of any sport, but certainly track and field. The powers that be with the Athletic Association didn't even want women training in the stadium because that was for football and men's track and field, both Fall and Spring. On more than one occasion, when we were using the stadium, we were locked inside. Sometimes we had to scramble to get over the gate or the wall just to practice."

Inequality continued in terms of the equipment they were—or rather were not—issued.

"We can talk about something as simple as buying a pair of shoes," Calabrese continued. "When I started college, I believe that minimum wage was $2.05, and in those days a decent pair of shoes cost $30 to $40. All of the women basically bought their own shoes. Also, there were a very limited number of uniforms. In using myself as an illustration with track and field, different events required different types of equipment. There were two discus that I had to practice with. They were rubber, undersized in weight, and laughably, (missing) big chunks. So it was really difficult to throw with any degree of accuracy because, aerodynamically, they didn't fly right. I had one javelin with the point cut off it, so you can imagine how that would fly. The only time I could use equipment that conformed with whatever the event was, was in an actual competition."

Then there was the issue of traveling to competitions.

"Typically, a track and field team might have 25-to-30 athletes for all the different events, but we might have had 15 uniforms and a travel budget for 12-to-15 women," Calabrese said. "When we went to a state or Big Ten competition, you're asking your discus thrower—i.e. me—to run (a leg) on the 800-meter relay. I was great for about the first 50 yards, but then it's like—duh—that must be the discus thrower. But track and field is a team sport and you have to win a certain number of events to win a tournament. The size of our roster all had to do with money.

"I qualified for the national championship—I believe it was in Texas," she continued. "We weren't allowed to leave two or three days early so we could have the benefit of being at that school's facilities to practice. (Instead) we left the night before and drove all night. I literally got out of the van and as I was running toward either the discus or javelin competition, they were actually calling my name. So, this was the type of stuff that we had to contend with."

The combination of all these inequities ultimately pushed Calabrese over the brink.

"I was young and fairly naïve about the law," she said. "If you're trying to be an advocate for change and you want to do so in an unoffensive and hopefully successful manner, you at least initially try to go through the proper channels. I believe I exhausted all of those channels over a period of six-to-nine months, including meetings with the women's athletic director (Karol Kahrs). It became very clear to me that nothing was going to be done. Certain changes would have to be done over a period of years and certainly I no longer would be an athlete at that particular point in time and thus would not have legal standing."

After exhausting those channels, Calabrese arranged a meeting with attorney Ed Rawles.

"This suit would not have been settled if not for this particular man," she said. "We had a couple of conversations and he agreed to take this on for women's sports and men's minor sports. It took close to two years before it was settled. I was maybe 19 when this started and I really thought that there was equal protection, at least under the law as the law existed. I came to find out that the law is really a lot about money, strategy, being in front of the right judge, having the right attorney, and loopholes. Really, it's much more of a game than a pursuit of justice. Shout out to Ed Rawles who helped to educate me in the law and who was persistent and tenacious.

"When the Athletic Association had exhausted all of its options, we were down to a two-week window where there was a court date," she said. "The ramifications to the U of I would have been significant and an embarrassment to the university—which was never, by the way, my intention—but that's what it was going to come down to."

That's when newly appointed Chancellor William Gerberding stepped in to arbitrate the dispute.

"He was someone who had more stature and control than the men's A.D. (Cecil Coleman)," Calabrese said. "(Gerberding) met with me and I think he was really flabbergasted as to what was going on and how long it had been going on and what the potential financial ramifications as well as the reputation of the university would be. He intervened and told Cecil Coleman and Karol Kahrs in no uncertain terms that there would be negotiations and a settlement, and this would not go to court. In one or two days of negotiations, it was settled."

Terms of the March 28, 1978, settlement stipulated that the support for qualified women's athletes—by payment of room, board, book expenses, tuition and fees, and tutoring—would be handled in a similar fashion as it was done for male athletes. It also required the same grades for men and women to be eligible for competition and for grants-in-aid, and it increased financial support for coaches of women athletes and for the expense of recruiting women athletes.

Furthermore, Gerberding committed that the university would underwrite some of the possible additional costs for a two-year period.

"It is easy in the afterglow to overlook the enormous amount of courage involved," Gerberding said when the settlement was announced. "Nessa and Nancy pursued this act in the face of an indifferent and hostile environment and against the advice of many who agreed with their ideas. It was a creative moment. The position of women wasn't merely moved ahead, but fundamentally transformed, and the University of Illinois is indebted to these two women and their attorney."

So, in Calabrese's opinion, what still needs to change for women's athletes in 2022 and beyond?

"Clearly, women's accomplishments in sports and women's ability through their notoriety in sport has not only transformed certain sports, but also the world," she said. "When I watch women's athletes today, their level of skill and accomplishment is amazing and tremendous. Scholarships, particularly in this day and age when higher education is so terribly expensive, have enabled certain young women with a dream to get an education and do the thing that they love. When you see the sport participation, it really blows me away and makes me happy.

"Now, all of that being said, what has not changed is that there is still a tremendous amount of discrimination, not just in sport but also in hiring practices and women's basic rights. What we've seen, in a very glaring way, is the extent to which discrimination still exists. It's very disheartening.

"I do not understand why women do not advocate for or support or champion for other women. Women in this country are a strong, formidable force. They have the power to move mountains and so many women have moved mountains individually. But if you want to orchestrate real change, you need to be united, be respected, be strong, and be courageous. And if you can't be courageous, then contribute in any way that you can. If you don't support each other, no one else will. It took hundreds of years for women to achieve what they have and it can be taken away from you in a very short period of time you don't fight for the things that are important and fair and just."

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/7/15/general-when-courage-moved-the-needle-for-illini-womens-athletics.aspx

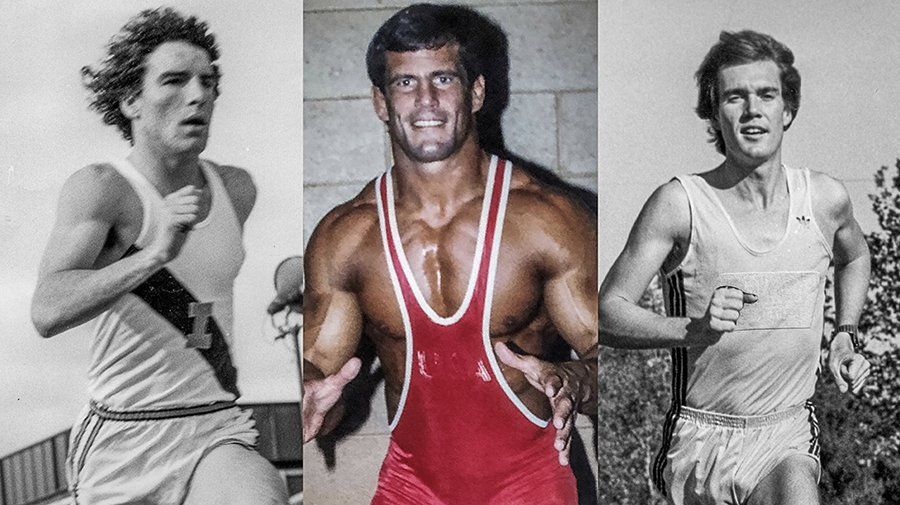

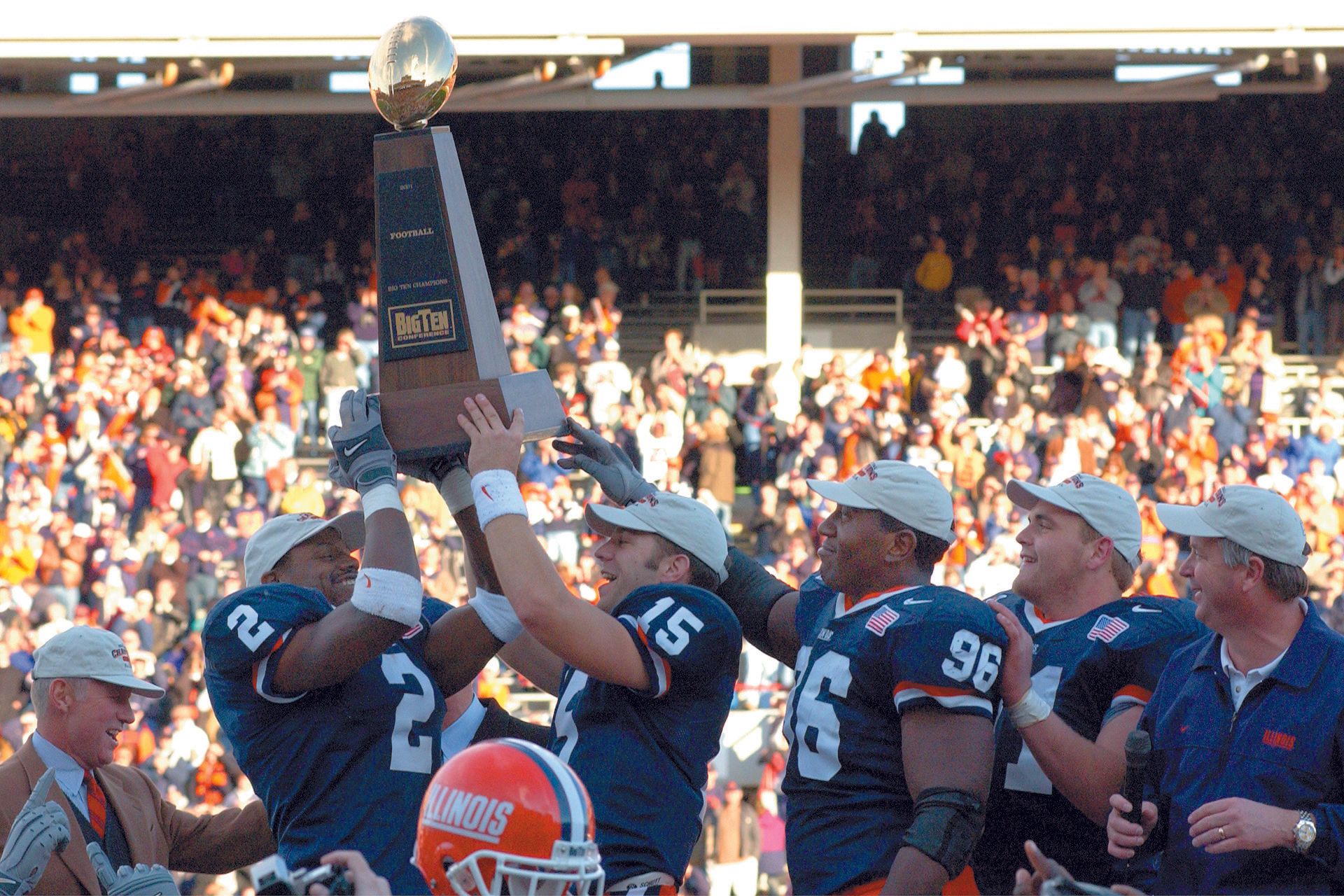

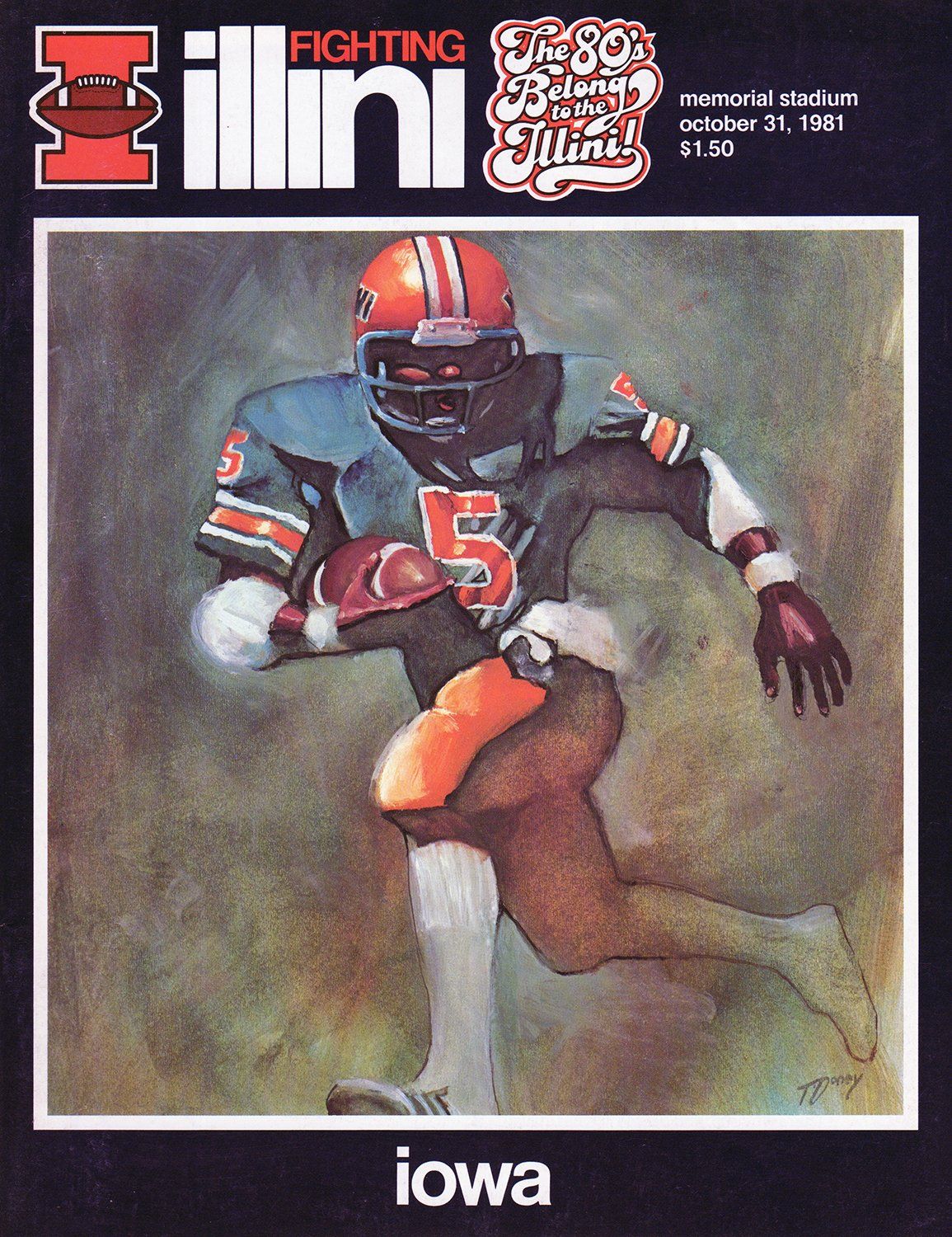

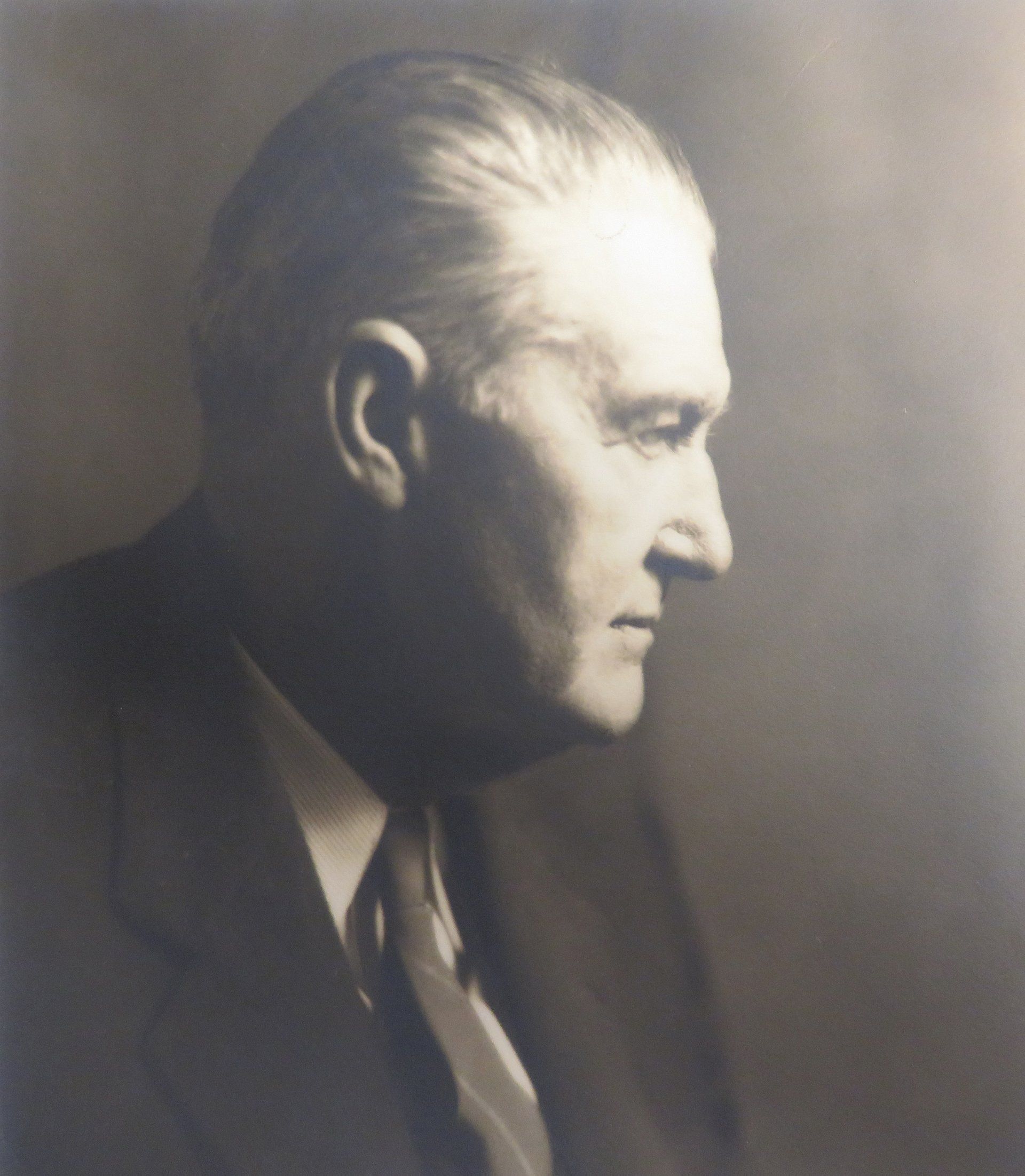

1990s Illini Stars

Decade of 1990s Propelled Illini Women’s Athletes to National Prominence

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

The third decade of University of Illinois women's athletics propelled the Fighting Illini into national prominence, including individual NCAA championships and multiple Big Ten Athlete of the Year recognitions.

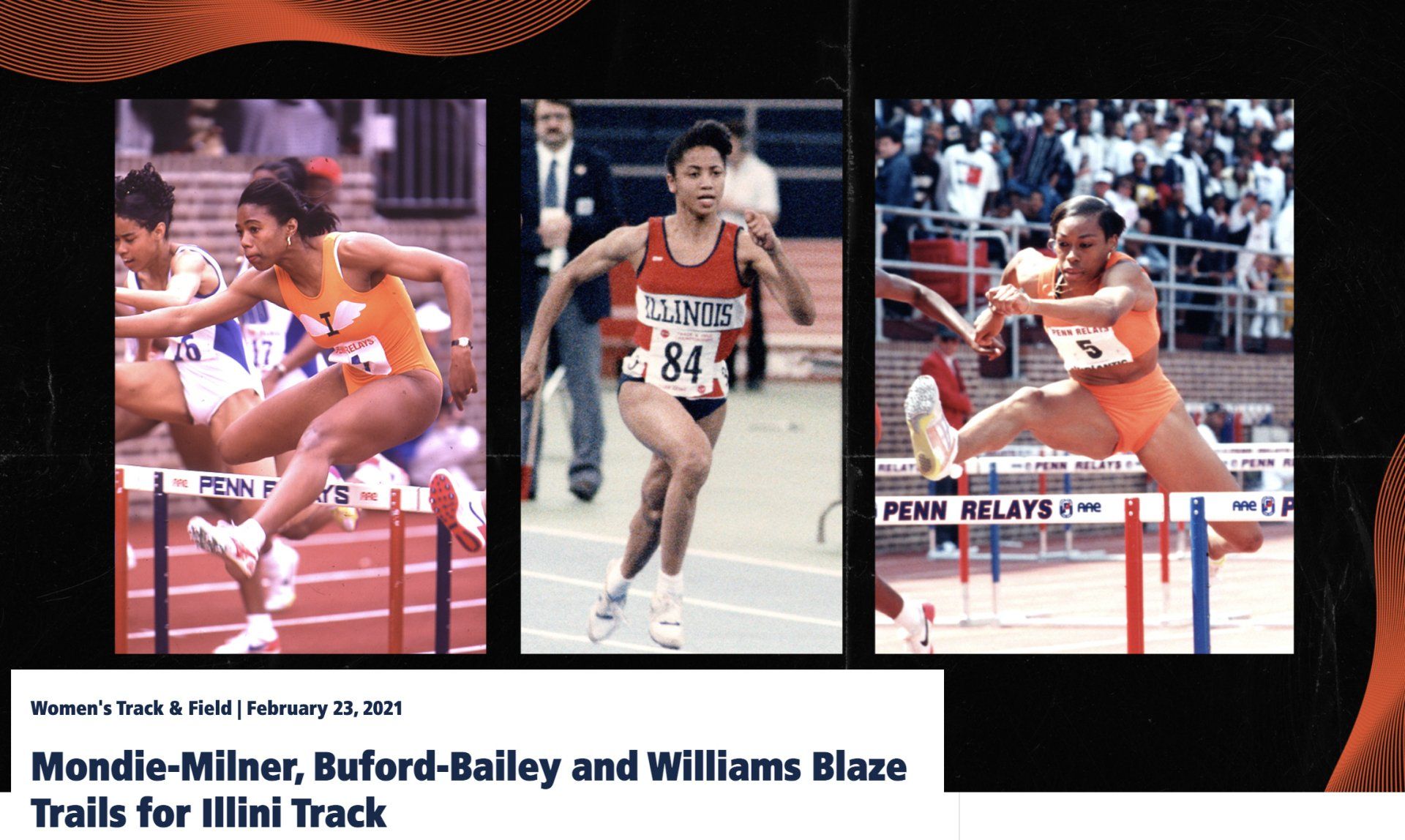

Significant accomplishments by volleyball, basketball, golf and track and field helped Illini publicists spread the word about the achievements of such athletes as Tonja Buford, Renee Heiken, Lindsey Nimmo and Ashley Berggren.

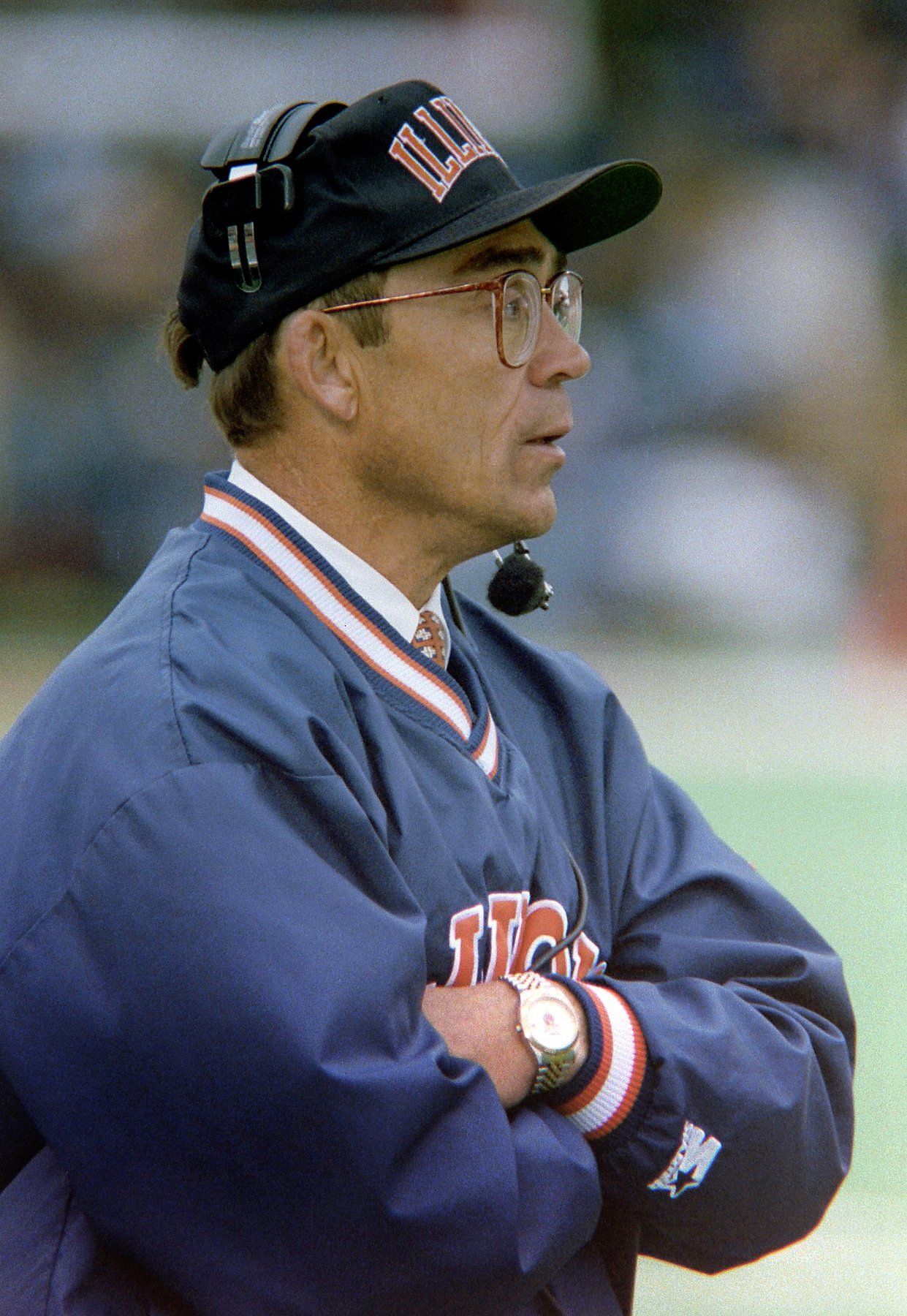

Additionally, newly appointed Illini Director of Athletics Ron Guenther was responsible for a flurry of coaching hirings, including basketball's Theresa Grentz and volleyball's Don Hardin. He also oversaw the creation of two new varsity programs—soccer and softball—and the selection of coaches Jill Ellis and Terri Sullivan.

Four new athletic facilities also were built for the latter two sports, plus facilities for basketball, track and field and tennis. The Bielfeldt Athletics Administration Building also was completed. Furthermore, during the 1990s, the volleyball program began hosting its competitions at Huff Hall.

Here is a chronological look at several of the most memorable Illini women's moments of the 1990s:

February 24, 1990: Illini women's track and field team athletes claimed six individual Big Ten championships enroute to tie-for-second-place finish.

March 24, 1990: The Fighting Illini women's gymnastics team won the Big Ten team championship, something it had never achieved before. Bev Mackes was named Big Ten Coach of the Year.

May 9, 1990: Illini hired Kathy Lindsey as its new women's basketball coach.

June 2, 1990: At the NCAA Championships, UI's Celena Mondie-Milner placed second in the 100-meter dash, while she and teammates Renee Carr, Tonja Buford and Althea Thomas finished second in the 4x100-meter relay.

September 4, 1990: Huff Hall debuted as the home of Illini volleyball. On hand for the special occasion were UI basketball's famed "Whiz Kids".

February 23, 1991: Illini team athletes claimed three individual Big Ten championships enroute to a second-place finish.

March 11, 1991: Basketball's Sarah Sharp named first-team All-Big Ten; Mandy Cunningham earned conference's Freshman of the Year honors.

May 5, 1991: Sophomore Renee Heiken won medalist honors at the Big Ten Women's Golf Championships.

May 18, 1991: Freshman Tonja Buford was named the top athlete at the Big Ten Outdoor Track and Field Championships, winning the 100 hurdles and running legs on the winning 400 and 1,600 relay units.

August 22, 1991: Illini women's gymnastics Big Ten uneven bars co-champion Lynn Devers was named NCAA State of Illinois Woman of the Year.

September 20, 1991: Cross country's Laura Simmering set an Illini record with a time of 16:46 at 5,000 meters.

September 28, 1991: The U of I celebrated the 10th anniversary of women's athletics in the Big Ten Conference.

November 2, 1991: Illinois dedicated its new $2.5 million Atkins Tennis Center.

January 26, 1992: Kathy Lindsay's basketball squad upset No. 18 Northwestern, 70-58.

February 29, 1992: Illinois' Tonja Buford claimed three individual titles (55m, 200m, 55m hurdles) at the Big Ten Championships as UI won team trophy.

May 3, 1992: Illinois' Becky Biehl earned medalist honors at the Big Ten Championships, shooting a four-round total of 319.

May 14, 1992: Ron Guenther was named Illinois' athletic director.

May 23, 1992: Tonja Buford won three individual events and ran a leg on the winning 4x100 relay team, leading Illinois to victory at the Big Ten Women's Track and Field Championships.

June 6, 1992: Buford won the 400-meter hurdles at the NCAA Championships, becoming the first Illini women's track athlete to win a national title.

August 2, 1992: Buford competed in Barcelona's 1992 Olympics, just missing the finals in the 400-meter hurdles event.

November 9, 1992: Illini volleyball's Kirsten Gleis named Big Ten Player of the Year.

November 28, 1992: Illini volleyball topped No. 22 Ohio State at Huff Hall, 3-0, extending UI's Big Ten winning streak to 18 straight. Illinois went on to win its first two NCAA Tournament matches before losing to No. 2 Stanford in the regional semifinals.

December 10, 1992: UI volleyball swept past No. 7 Nebraska in NCAA Tournament play, improving its record to 32-3. The next day, a record crowd of 4,316 watched UI lose in four sets to No. 2 Stanford.

December 16, 1992: Illini volleyball's Kirsten Gleis named first-team All-America, Tina Rogers second-team.

March 6, 1993: Victories in the 55 dash, the 55 hurdles and the 200 dash by Tonja Buford led Illini women's track and field to a 41-point team victory over Wisconsin at the Big Ten Championships.

May 2, 1993: Tennis's Lindsey Nimmo was named Big Ten Women's Player of the Year, leading Illinois to a program-best second-place finish in the Big Ten.

May 7, 1993: Following 16 years of service, Bev Mackes retired as head women's gymnastics coach.

May 9, 1993: Renee Heiken shot a final-round 73 and captured medalist honors for the second time at the Big Ten Women's Golf Championships.

November 30, 1993: Tina Rogers and Kristin Henriksen won first-team All-Big Ten honors for the second straight season.

February 18 & 19, 1994: Senior swimming Jennifer Sadler set varsity records in the 50 and 100-yard freestyle at the Big Ten Championships.

February 26, 1994: Five individual titles helped Illini track and field team finish second at the Big Ten Championships.

October 21, 1994: Ground was broken for the construction of the Bielfeldt Athletics Administration Building. It was dedicated on Oct. 4, 1996.

November 29, 1994: Volleyball's Julie Edwards won first-team All-Big Ten honors.

February 26, 1995: Four individual titles, including two in the long jump and pentathlon by Carmel Corbett, helped Illini track and field team win the Big Ten Championships.

May 15, 1995: Theresa Grentz was named as the new Illini women's basketball coach.

May 21, 1995: The Illini women's track and field squad won eight of the Big Ten Championships' 19 events and crushed runner-up Wisconsin in the final team standings, 163-112.

May 31, 1995: Illinois and Nike announced a new multi-million-dollar deal.

June 2, 1995: Tonya Williams became only the second Illini woman to win an NCAA outdoor title, capturing the 400-meter hurdles event.

September 23, 1995: Erin Borske's single-march record 44 kills led Illini volleyball past Penn State.

November 24, 1995: Illini defeated UNC-Greensboro in Coach Theresa Grentz's coaching debut.

December 13, 1995: Erin Borske won first-team All-America honors.

December 27, 1995: Volleyball's Mike Hebert resigned from his post as Illinois' head coach to assume a similar position at Minnesota. On January 19, 1996, Louisville's Don Hardin was named as his replacement.

January 19, 1996: Illini basketball destroyed No. 14 Arkansas, 88-64.

February 8, 1996: The 100th anniversary of the founding of the Big Ten Conference was observed.

February 25, 1996: Six individual titles, including two by Dawn Riley, led Illini track and field team to its fourth indoor Big Ten team title in the last five years.

March 1, 1996: Illini basketball won its first-ever Big Ten Tournament game, topping Indiana, 84-70.

May 31, 1996: Illinois' Tonya Williams captured the NCAA 400-meter title.

December 29, 1996: Illini women's basketball upset No. 16 Wisconsin, 73-67, led by Ashley Berggren's 23 points.

January 8, 1997: Ashley Berggren's 23 points and 20 more from Alicia Sheeler helped Illinois blitz No. 10 Arkansas, 100-81.

January 30, 1997: UI named Jillian Ellis as the first Illini soccer coach.

February 14, 1997: The Illini women's basketball team won a Big Ten game for the 11th time in its last 12 opportunities, beating host Ohio State, 84-81. Illinois went on tie for the Big Ten title, its first ever, and battle its way into the NCAA's Sweet Sixteen.

February 23, 1997: A record-breaking crowd of 16,050 at the Assembly Hall watched Illini women's basketball host Purdue.

March 1, 1997: Theresa Grentz was named Big Ten's Coach of the Year, Ashley Berggren Player of the Year.

March 2, 1997: Illini women's basketball topped Michigan State in the semifinal round, 77-66, to qualify for its first-ever championship game appearance. Iowa defeated Illinois in the championship game, 63-56.

March 14 & 16, 1997: Illini basketball defeated Drake (79-62) and Duke (85-67) at the NCAA Tournament. They were eliminated by top-ranked UConn six days later.

March 27, 1999: Illini gymnastics' Gina Weichmann won the Big Ten championship in balance bar.

September 5, 1997: Illini soccer's first-ever game ended with a 4-0 shutout against Loyola.

October 14, 1997: Soccer's Rachel Smith scored three goals in one half against Aurora, leading Illinois to a record-setting 10 goals (10-1). This still stands as a record for largest margin of victory.

December 8, 1997: Illini basketball placed No. 5 in the Associated Press poll, its highest ranking ever. Four days later, UI lost at No. 1 Tennessee, 78-68.

December 28 & 30, 1997: Illini basketball defeated No. 22 Purdue and No. 11 Wisconsin in back-to-back games.

February 27, 1998: Ashley Berggren was named Illini MVP for a record third consecutive time. Theresa Grentz was honored as Big Ten's Coach of the Year.

March 9, 1998: Ashley Berggren named third-team All-America, becoming the first UI player to attain national honors.

March 14 & 16, 1998: UI basketball opened NCAA Tournament play with back-to-back victories over Wisconsin-Green Bay and UC-Santa Barbara. The Illini placed 14th in the final national poll.

March 21, 1998: Ashley Berggren ended her career as UI's all-time leading scorer (2,089 points).

October 8, 1998: Illini women's basketball team practiced for first time at UI's new Ubben Center.

November 5, 1998: Junior midfielder Kelly Buszkiewicz became the first Illini soccer player to win first-team All-Big Ten honors.

November 19, 1998: Basketball opened its season with 76-58 victory at No. 19 Stanford.

December 4 & 5, 1998: Coach Don Hardin's Illini volleyball team beat Southwest Texas and No. 17 Colorado to open NCAA Tournament play.

December 19, 1998: Basketball stunned No. 14 Florida, 97-77.

February 28, 1999: Illini women's basketball defeated nationally ranked Penn State for a second time, winning by a score of 77-75 on a last-second shot at the Big Ten Tournament. It lost to Purdue the next day in the championship game, 80-76.

June 23, 1999: Terri Sullivan was named Illinois softball's first coach.

July 7, 1999: Tricia Taliaferro was named Illinois soccer's second coach.

August 27, 1999: Illinois christened its new soccer field with a 3-1 victory over Marquette.

September 14, 1999: Illini soccer was included in the national rankings for the very first time, placing 21st in the National Soccer Coaches Association poll.

September 19, 1999: Illini soccer defeated No. 12 Wisconsin, 3-1, UI's first-ever victory over a ranked opponent.

November 27, 1999: UI's women's basketball team beat No. 6 Notre Dame in South Bend, 77-67. Three days later, UI lost at No. 1 UConn.

December 18, 1999: Illini basketball beat No. 20 Kansas, 61-59, in their first-ever game at the United Center.

This feature and additional photos also can be viewed at FightingIllini.com.

https://fightingillini.com/news/2022/7/7/general-decade-of-1990s-propelled-illini-womens-athletes-to-national-prominence.aspx

Nancy Thies Marshall & her family

Growing Up Nancy Thies

By Mike Pearson

Pearson is a staff writer for the Division of Intercollegiate Athletics and author of ILLINI LEGENDS, LISTS & LORE (Third Edition).

Young teenage girls have a myriad of challenges with which to deal, including appearance and self-esteem, developing friendships and surviving bullies, peer pressure, and the physiological evolution of their bodies.

And while young Nancy Thies (Marshall) dealt with all of that, the multi-talented Urbanian who grew up at 2115 Boudreau Drive also was training to become a world class athlete in gymnastics.

At the tender age of 15, she became an Olympian, performing at the 1972 Games in Munich, Germany against gold medal winners Olga Korbut and Ludmila Tourischeva. The future Illini gymnast and Big Ten champion is credited with being the first person to perform back aerial tumbling on the balance beam in Olympic competition.

During her multi-faceted career, Nancy has worked for NBC-TV as an analyst, authored athletic-themed books, volunteered and led nonprofit organizations, and served on numerous advisory boards. She retired in 2020 as the Director of Human Resources at Corban University in Salem, Ore. Nancy married Charlie Marshall in 1981 and they have three children and four granddaughters.

In 2010, she was inducted into the World Acrobatic Society Hall of Fame, and in 2017 became a charter class member of the University of Illinois Athletics Hall of Fame.

In a recent interview, Marshall discussed the beginnings of her athletic career, capped by her performance as an Olympian.

You grew up in Urbana on Boudreau Drive, which is parallel to Grange Drive and in the same neighborhood as Zuppke Drive and George Huff Drive. When you were growing up, did you make the connection of these names to Illini lore?

I did because I sat around the table with two parents (Dick and Marilyn) who attended the U of I in the early '50s and I had grandparents who attended the U of I in the '20s. At many of our gatherings we would talk about the role that some of these people played. When I was young, Charlie Pond was still a big part of the U of I. My Mom and Dad would talk about the great success that he had. My own coach, Dick Mulvihill, was a protege of Charlie's.

Part of my desire and passion to go to the U of I was that I could bring something to this story about the beginning of women's athletics. I speak with deep respect for the fact that other women had opportunities to do sport but not on the competitive and sanctioned level that was now, all of a sudden, opening up. So, for me, part of my narrative was this hope of going to my school, my hometown school … could I do something that would help build back that culture of excellence and that culture of success.

I knew I was one of two Olympians to participate in this next chapter of women in sports. I wanted more to come to the U of I and try to be a part of something on the ground level than to delay my freshman year and train for the '76 Olympics. That was the decision I made in '75.

As pre-teens, many young girls aren't all that far removed from playing with dolls and watching cartoons. So how old were you when gymnastics entered your routine?

I had some sort of gymnastics lessons from a ballet teacher here in Urbana when I was six. Our YMCA (McKinley) had the gymnastics program that Dick Mulvihill started and I began that at age eight. In some ways, my experience with competitive sports is an anomaly when you look at this great big, grand picture of the development of women's sports.

If you look at the Olympic level, you already had some programs for women in track and field, swimming and diving, and a few other sports. So those sports, even though they weren't necessarily being administered through a collegiate lens, were a bit more developed in terms of opportunities for women. At age 11—right after the '68 Olympics—Dick Mulvihill sat me down in the gym (in the basement of Lincoln Square). I remember the conversation. He said, 'Nancy, you're 11, but in four years you'll be old enough to go to the Olympics. I think you can go, but this is what it's going to take.' And at 11, I kind of was answering that question.

My sister Ann, who's nine years younger than me, is actually the best athlete in the family. She graduated from high school in 1984, so she got to experience on a high school level much more the development of women's sports. My sister, Suzie, ran track at Urbana in those beginning years of competitive sports. She went to Indiana and she and four others are the women who demanded a women's track team at Indiana University. They got the women's track team started under Sam Bell. So we have a lot of stories in our family about those years and how it affected the three girls in our family.

Because you were so young, did gymnastics steal away any of your childhood?

That's a good question to ask a 64-year-old. For 60 years of my life, I've always said 'Heavens no. It didn't steal it … it enhanced it.' Maybe I say that because I had parents who were so committed to my life beyond gymnastics.

In our family, gymnastics was always seen through a lens of 'How is this going to enhance our lives?' Not just mine, but also my siblings' and my parents' lives. While it wasn't always in the budget to take everyone to every meet, we were always taking advantage of those meets.

One meet that was in Philadelphia in which I competed—USA versus the French National Team—my brother, David, went along because he was studying French at Urbana High School. He loved the experience as much as I did. Then, my sister, Suzie, traveled to Oregon with me when I was training there. My parents always did whatever they could to make my experiences enhance all of our lives.

I don't know that gymnastics necessarily stole my childhood away. I've often been asked to talk to young women and I will often use a phrase to begin my talk … about if my 64-year-old self could talk to my 15-year-old self. Of course, there are always things that I would do differently, but I think it opened up doors and sent me places that I never, ever would have gone. I'm so grateful for that.

Gymnastics allowed you to travel world-wide … unbelievable experiences, right?

I often will describe my gymnastics experience a little bit like a Forest Gump (metaphor). Until the day he died, Dick Mulvihill would describe me as the one Olympian that he trained that walked into the gym with two left feet. I think he saw me as sort of this challenge as someone who people thought could never make it to the Olympics.

I was never the star. Even on our local YMCA team, I was number four, five or six on the team. Though I worked hard, I made the Olympic Team in '72 because some of those ahead of me got injured or decided to be done. I kept moving up the ranks and there was a spot for me. When I think about going to the Soviet Union and South Africa and the (1973) event that happened with the Chinese piano player, all of those were brushes with a much bigger story than my own. It's probably one of the reasons why I went into history and journalism in college because those stories were so fascinating to me.